John Vassiliou. This blogpost was originally posted on Free Movement. We are reposting with permission of the author and the editors.

Upholding an earlier High Court decision, the Court of Appeal has confirmed that the Home Office’s £1,012 fee for registering children as British citizens is unlawful. The case is R (Project for the Registration of Children As British Citizens & Anor) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2021] EWCA Civ 193.

The challenge succeeded on the ground that the Secretary of State failed to discharge her duty under section 55 of the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 to have regard to the need to safeguard and promote the welfare of children when setting the fee. This is a massive win for the claimant ‘O’, for the Project for the Registration of Children as British Citizens (PRCBC), and for their legal teams.

Profiteering from children’s rights

£372 is what it costs the government to process an application for a child’s registration as a British citizen. £1,012 is what it charges. That’s a whopping £640 profit (the Home Office hates that term, incidentally) on each application. And that’s not counting the additional mandatory £19.20 biometric enrolment fee. And the UKVCAS biometric enrolment appointment fee, which can come in at up to £200.

Citizenship is important to a child. The Home Office agrees:

Becoming a British citizen is a significant life event. Apart from allowing you to apply for a British citizen passport, British citizenship gives you the opportunity to participate more fully in the life of your local community.

Guide T at page 3

And the Court of Appeal definitely agrees:

it is not disputed by anyone, least of all by the Secretary of State, that British citizenship is a status of importance to those that hold it and that the entitlement to be registered as a British citizen is likewise a right of importance.

Lord Justice David Richards, paragraph 32.

Notwithstanding the undisputed importance of citizenship, for years now the government’s policy has been clear: “Citizenship registration fees are charged as part of a wider fees approach designed to reduce the burden on UK taxpayers”. In other words, the Home Office deliberately inflates citizenship fees well above the actual cost of processing, in order to derive a profit that can be used to offset departmental costs in other areas of immigration control.

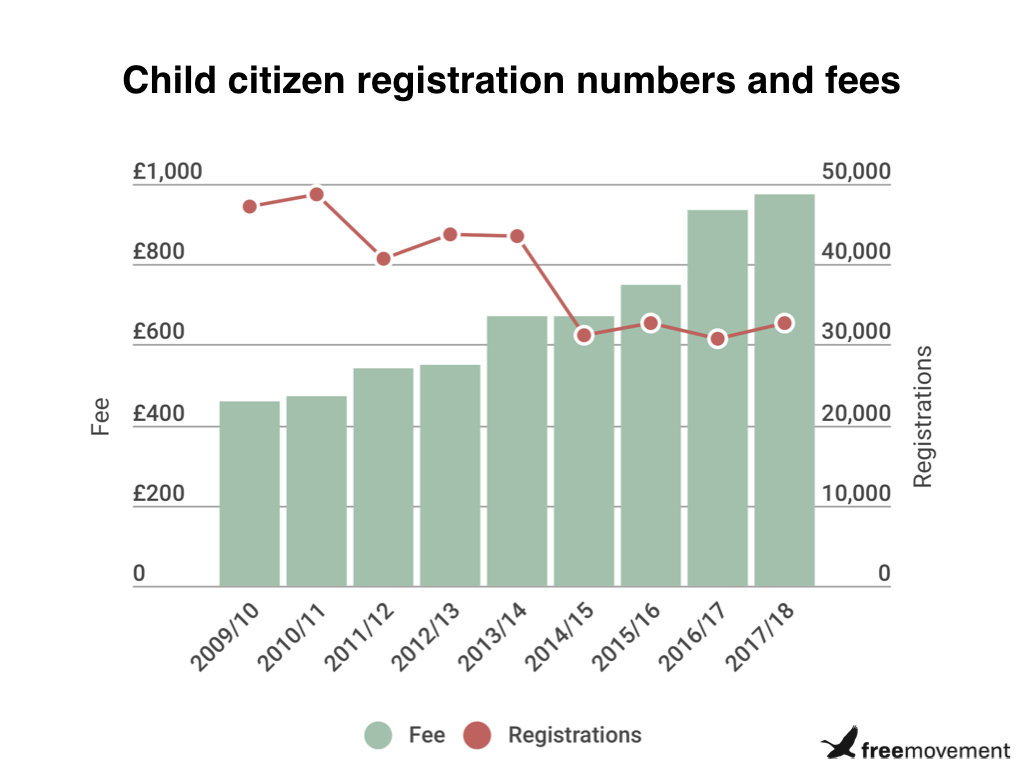

In the face of aggressive year-on-year price hikes which saw registration fees leap from £699 in 2014 to £1,012 in 2018, a significant number of children have been priced out of their entitlement to British citizenship. This fact is also undisputed by the Home Office.

Who has to pay these registration fees?

Before we get into the court’s reasoning, some nationality law background. When we talk about registration in the context of British citizenship, we are not talking about passport applications for children who are automatically born British. We are also not talking about adult naturalisation applications. Registration in the context of British citizenship is, generally, an entitlement to citizenship which one must apply for to get. No application, no citizenship.

For children who are not born British, there is often a statutory entitlement under the British Nationality Act 1981 to be registered as British, upon application and if certain conditions are fulfilled after their birth. It is these children, or realistically their parents/carers, who must pay the Home Office’s child registration fee.

What are the criteria for registering a child as British?

The two most common grounds for registration of children born in the UK are:

Section 1(3)

A person born in the UK who is not automatically a British citizen is entitled to be registered as a British citizen if, before they turn eighteen, their father or mother become British or settled in the UK, and an application is made for registration. Once the person turns 18, they lose the ability to apply to register under this section. For children in this situation, it is imperative that their parents are able to finance an application before the child’s 18th birthday.

Section 1(4)

A person born in the UK who is not automatically a British citizen is entitled to be registered as a British citizen at any time after the age of ten, if in the first ten years of their life they have not been absent from the UK for more than 90 days in any year. This type of registration remains available to adults even after the age of 18.

There is more on registration in the Free Movement Introduction to British nationality law training course (which John is too modest to mention that he wrote — Ed.)

The claimant, ‘O’

O was born in the UK in July 2007 and had never left the UK. She is a Nigerian citizen by descent from her parents. As soon as she turned ten, she fulfilled the substantive criteria for registration as a British citizen under section 1(4) of the British Nationality Act 1981.

She is however one of three children living with their single-parent mother. The family is destitute and has been financially supported by their local authority since 2015. Her mother was unable to raise the (then) registration fee of £973. With the assistance of the PRCBC, she instead submitted an application with just an accompanying fee payment of £386 (the administrative cost at the time).

O’s application was refused and has been the subject of litigation ever since. Alongside O, there was another individual claimant, ‘A’, whose claim has since been settled.

The Court of Appeal’s reasoning

The child’s best interests challenge

Echoing the findings of the High Court, the Court of Appeal agreed that the Secretary of State had failed to conduct any kind of assessment of the best interests of children in setting the registration fee. Embarrassingly, in the course of proceedings, the Secretary of State completely gave up on her own witness’s evidence on the child’s best interests. Wisely so, with the Court of Appeal endorsing Mr Justice Jay’s conclusion in the High Court: “I would unhesitatingly conclude that the Secretary of State has fallen far short of satisfying me that the section 55 duty had been discharged”.

Instead the Secretary of State tried to rely on the contents of Parliamentary debates to show that the best interests of children had been considered in setting the fees. This resulted in a rather unusual opening line to the judgment:

At the hearing of these appeals, the court raised with the parties whether the reliance by the Secretary of State on the contents of debates in both Houses of Parliament in the court below and before us contravened Article 9 of the Bill of Rights 1689 and the rules of parliamentary privilege.

Paragraph 1

Both the Speaker of the House of Commons and the Clerk of Parliaments were invited to intervene, and intervene they did, taking the view that the Secretary of State’s use of materials fell outwith any permissible exceptions to the rules on parliamentary privilege. The court agreed. Reliance on Parliamentary materials was not permitted:

… it was surprising that the Secretary of State had not conducted the reviewnecessary for the performance of her duty under section 55 outside Parliament. If she had done so, she would have been able to give evidence of it in a witness statement, and the issue of Article 9 and Parliamentary privilege would not have arisen.

Paragraph 110

The High Court’s decision to declare that the Secretary of State breached her duty under section 55 when setting the child registration fees was upheld.

The ultra vires challenge

A second, broader challenge to the lawfulness of the Immigration and Nationality (Fees) Regulations 2017 and 2018 was rejected, however. The claimants argued that so long as an unrealistically high registration fee persists, the registration entitlement is effectively null and void. Without the ability to pay the fee, the ability to benefit from the entitlement is lost. Thus the regulation is unlawful because it is ultra vires (Latin: beyond the powers) the fee-setting power conferred by section 68 of the Immigration Act 2014.

This challenge was rejected by Jay J in the High Court, because he was bound by higher authority from the case of R (Williams) v SSHD [2017] EWCA Civ 98. He had authorised an unusual “leap-frog” appeal on this point straight to the Supreme Court, but the Supreme Court kicked it back down to the Court of Appeal to consider in light of its post-Williams decision in R (UNISON) v Lord Chancellor [2017] UKSC 51.

The Court of Appeal has now considered this point, and concluded that it continues to be bound by the ratio of Williams. So the direct challenge to the vires of the fee regulations must be dismissed.

The mood music from the court could not be clearer, though:

If the matter were free from authority, I would see considerable force in the submissions made by Mr Drabble QC on behalf of the Respondents but I agree with David Richards LJ that the decision of this Court in Williams is binding on this Court.

Paragraph 119

Consequences

If the case were to be left as it were now, the Secretary of State would have to undertake a review of the fee regulations and, in so doing, give consideration to the children’s best interests. Call me cynical, but she would likely end up concluding that the registration fee should remain unchanged.

Thankfully this is not where this case ends. The Court of Appeal has already granted permission for the claimants to appeal to the Supreme Court on the ultra vires ground.

I am not clear yet whether the Secretary of State also intends to seek permission to appeal on the best interests point. From it what the Home Office’s spokesperson confirmed to the Independent, it sounds like it may not.

The Home Office acknowledges the court’s ruling and will review child registration fees in due course.

Still, until this very positive decision is translated into practical change, the child registration fee for anyone applying today remains at £1,012 plus extras. Parents of younger children with a secure immigration status may wish to hold off on making registration applications until the Supreme Court rules on this case (although that can take quite some time). Parents of older children nearing the age of 18 who cannot afford to pay the registration fee should consider seeking legal advice.