Eva Ersbøll (Danish Institute for Human Rights)

The Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR) recently published a report based on a study on access to Danish citizenship for children and young persons who are born and/or raised in Denmark. The study, titled Alien in one’s own country?, is based on interviews with 22 young persons among whom, 11 are born in Denmark and most of the others have come to Denmark during their early childhood. The respondents have given a recount of their experiences of growing up in Denmark as ‘foreigners’ – in other words, as individuals without Danish citizenship and without any prospect of facilitated access to Danish citizenship. Their stories have inspired the title of the report since they experience a sense of alienation triggered by a long and complicated naturalisation process.

The report includes a qualitative, a quantitative and a legal analysis based on which, the report concludes and recommends Danish law to be amended with a view to provide for facilitated access to Danish citizenship for 1.5, second and third generation of immigrant descent. As the report is written in Danish, this post provides a brief summary of the content of the report.

No independent right to Danish citizenship before majority

As a rule, children of immigrant descendance cannot independently apply for Danish citizenship. As minors, they may acquire Danish citizenship by filial extension when a parent acquires Danish citizenship, normally by naturalisation. However, if a child’s parents cannot or will not naturalise, the child must reside in Denmark based on a temporary residence permit. Only at majority, it is possible to apply for a permanent residence permit and subsequently Danish citizenship.

No facilitated access to Danish citizenship

Traditionally, second generation has been entitled to Danish citizenship at majority, and according to the state of the law up to 2004, persons who had resided in Danmark for ten years in total before the age of 18 – 23 were entitled to Danish citizenship by declaration, conditioned by the absence of a criminal record. This rule was repealed in 2004, and today, only descendants with a Nordic citizenship are entitled to Danish citizenship by declaration. Other descendants (1.5, second and third generation) must apply for Danish citizenship by naturalisation and fulfil the same requirements as apply to first-generation immigrants.

Strict naturalisation requirements

In Denmark, naturalisation is granted by Parliament by law, and the requirements are restrictive. Citizenship may be granted to foreigners with a permanent residence permit, normally after at least nine years of residence, good conduct, no charge of a criminal offence, no debts to the state, certification of knowledge of the Danish language (normally level B2 or Danish school leaving exam), the pass of a citizenship test, and proof of self-support (no cash benefit for two years prior to the presentation of a naturalisation bill in Parliament and not more than four months’ cash benefits within the last five years).

Permanent residence requirement may postpone naturalisation

Young persons who have turned 18 but not yet 19 may qualify for a permanent residence permit on lenient conditions. To quality, they must since completion of primary school have worked full-time or studied continuously when applying. Those who cannot fulfil this requirement must meet the general conditions applying to applicants older than 18 years. Then, the most demanding requirement is that they must have had regular, full-time employment or self-employment in Denmark for at least 3 and a half years during the last 4 years prior to the grant of the permanent residence permit. For young persons who want further education, this means that they cannot acquire a permanent residence permit until they have completed their education and subsequently have worked full-time for three and a half years. Effectively, this requirement may postpone their acquisition of a permanent residence permit (and Danish citizenship) until they reach the age of 30 years or more.

Experiences of the naturalisation process

None of the 22 interviewees had acquired Danish citizenship during their childhood since none of their parents had naturalised by then. Later, some of the parents had acquired Danish citizenship and therefor, some of the respondents had younger siblings with Danish citizenship (acquired by extension). Still, most of the parents had not naturalised, either because they were not able to fulfil the naturalisation requirements or because they did not want to give up their citizenship of origin.

The interviewees explained that the lack of a Danish passport had created problems for them both during school time and later. They had not been able to travel abroad on equal terms with their classmates and they were prevented from taking certain jobs and from studying abroad. In addition, many underscored the frustration they felt being prevented from voting in parliamentary elections.

Some of the informants had acquired Danish citizenship as adults (nine in total), while others were still struggling to acquire a permanent residence permit. Although most of them had grown up in Denmark with a sense of belonging, they felt alienated by the naturalisation process that required proof of their attachment to Denmark. The obligation to prove what they considered to be obvious, triggered questions on their Danish identity and belonging. They did not find it difficult to comply with the Danish language requirement, and neither did those who had enrolled for the citizenship test find the test difficult to pass. The necessity of testing their worthiness to become Danish and the fact that their endeavours so far could not be accepted as a sufficient proof of their belonging were considered problematic. In this regard, they compared themselves with their Danish friends with whom they shared a common background, being born at the same hospitals and educated in the same institutions, schools and universities.

In general, the acquisition of Danish citizenship meant a lot to the respondents, even if it did not strengthen their feeling of being Danish. They felt Danish long before they formally were granted Danish citizenship. At that occasion, many were relieved that the long application process had ended, while others expressed mixed feelings, since the citizenship certificate reminded them of the troublesome application process.

Statistics

The study’s quantitative analysis highlights the intergenerational effect of more and more restrictive naturalisation reforms, which has recently also been explored by Marie Labussière and Maarten Vink in a paper on the case of the Netherlands.

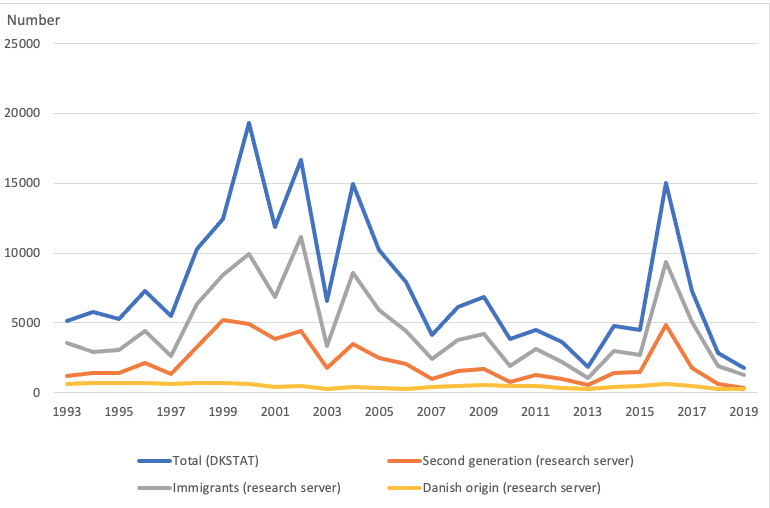

In Denmark, we see the same tendencies as have been shown in the Netherlands. The data show that concurrently with more restrictive legislative changes, the annual grants of Danish citizenship have fallen from about 15,000 in 2004 to below 3,000 (see Figure 1) in 2018 and 2019. Simultaneously, the total share of immigrants with Danish citizenship has decreased from about 37 percent to 26 percent, while the estimated residence period in Denmark before immigrants acquire Danish citizenship has risen from an average of about 11 years to an average of about 19 years (see here and also here a recent paper on the long-term consequences of citizenship policy, comparing Denmark to the Netherlands and Sweden).

Figure 1. Acquisition of citizenship in Denmark, 1993-2019, by origin

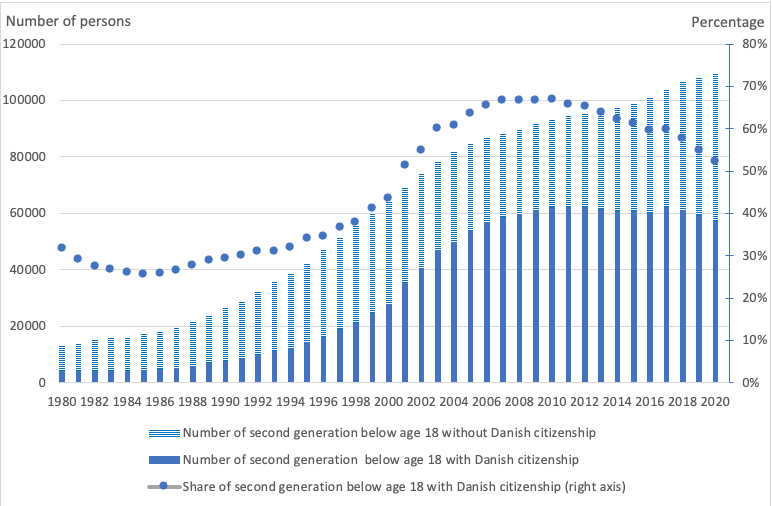

This development has a spillover effect on immigrant descendants’ acquisition of Danish citizenship through their parents (by extension or transfer). First, the percentage of children who have acquired Danish citizenship as minors has fallen from 19 to 8 percent for 1.5 generation and from two-thirds to 52 percent for the second generation (see Figure 2). Second, the share of zero-year-old immigrant children with Danish citizenship (acquired at birth by descent after birth by extension) has fallen from 53 percent to 26 percent [figure 4]. Third, among children who have immigrated to Denmark together with their parents (1.5 generation), very few who have arrived at the age of six years or more have acquired Danish citizenship during their childhood (2 – 5 percent).

The share of adult descendants with Danish citizenship have risen to 82 percent for second generation and 92 percent for third generations.

Figure 2. Second generation below 18 years and their citizenship

Analysis and recommendations

Equal right to Danish citizenship by declaration

Denmark has ratified the European Convention on Nationality, which requires (cf. article 6(4)(e) and 6(4)(f)) that the state shall facilitate the acquisition of its citizenship for persons, who are lawfully and habitual residents and either born on the state’s territory or resident there for a certain period during childhood.

Denmark has not fulfilled this obligation, since persons who are born in Denmark or who have migrated to Denmark as small children cannot acquire Danish citizenship on lenient conditions. Notably, as a group they do not benefit from a facilitation of the residence requirement allowing persons who have immigrated to Denmark before the age of 15 to apply for Danish citizenship at the age of 18. Therefore, facilitations must be introduced. The DIHR recommends that the necessary changes are implemented by an amendment of the Danish Nationality Act’s sect. 3 with a view to provide for equal acquisition of Danish citizenship by declaration for all immigrant descendants aged 18 – 23, regardless of their national origin. Arguably, the preferential treatment of Nordic descendants, who are entitled to Danish citizenship by declaration, compared to non-Nordic descendants, who must naturalise, may raise an issue under the European Convention of Human Rights article 14 taken in conjunction with article 8, cf. the case law of the European Court of Human Rights, among others Genovese v. Malta (see also an older post on how this case was interpreted by the Austrian Constitutional Court) . Along the same lines, René de Groot has argued that access to the citizenship of a state with which an individual has a genuine link based on birth on the territory or residence there for a longer period should be given in a non-discriminatory way.

Children’s right to a permanent residence permit and citizenship

Children born and/or raised in Denmark cannot be issued a permanent residence permit and as a rule, they cannot apply independently for Danish citizenship before majority. Therefore, many children in primary and secondary school experience problems with travelling abroad, and at the age of 18, many feel alienated because they must apply for a residence permit to stay legally in the country they consider theirs. Notably, due to the intergenerational effect of the restricted naturalisation requirements, this problem applies to more and more immigrant descendants.

Against this background, the DIHR recommends Danish legislation to be amended with a view to grant children of immigrant descent the possibility to acquire a permanent residence permit and moreover, to provide children at a certain age the possibility to apply independently for Danish citizenship.

For more information on citizenship legislation in Denmark, see the GLOBALCIT country report on citizenship law in Denmark by Eva Ersbøll.