Representing European citizens: Why a European Citizens Assembly should complement the European Parliament, kickoff contribution by Kalypso Nicolaidis

Why Citizens’ Assemblies should not have Decision-making Power, by Cristina Lafont and Nadia Urbinati

Empowering European Citizens but Avoiding Illusionary Promises!, by Sandra Seubert

Can a European Citizens’ Assembly Improve Political Equality and Overcome the Demoi-cratic Disconnect?, by Richard Bellamy

Would a European Citizens’ Assembly Justify a Sense of Democratic Ownership?, by Svenja Ahlhaus & Eva Schmidt

Democracy 3.0 in the 21st Century: the Case for a Permanent European Citizens’ Assembly , by Yves Sintomer

Grounding ‘Democratic Innovations’ in Wider Decolonial Movements Within and Beyond EU Borders, by Alvaro Oleart

The advantages and perils of a civil-society-led European Citizens’ Assembly, by Brett Hennig

How to Make Citizens’ Participation Successful: The Case for Citizens’ Panels on Key Commission Proposals, by Daniel Freund

Can a Complementary ECA Democratise European Democracy?, by Jelena Dzankic

The Two European Demoi: Authorizing EU Legislation and Deliberating on Affected Interests , by Rainer Bauböck

Perceptions and Practicalities of a Standing European Citizens’ Assembly, by Anthony Zacharzewski

Rotation, task definition and an increased membership: an alternative imaginary for a permanent ECA, by Graham Smith and David Owen

Connecting to publics: challenges and possibilities for the European Citizens’ Assembly, by Melisa Ross and Andrea Felicetti

Enlarged Complementarity : How an ECA Should Relate to Other Institutions and Actors, by Lucile Schmid

Why a European Citizens’ Assembly Should Replace Sortition with Liquid Democracy, by Chiara Valsangiacomo and Christina Isabel Zuber

Rome was not built in one day, neither will a European Citizens’ Assembly, by Camille Dobler and Antoine Vergne

Democratisation through Europeanisation: the Case for a Permanent EU Citizens’ Assembly , by Alberto Alemanno

Mind the Gaps: Scaling up Digital Spaces to Increase Translocal Porousness in an ECA , by Andrea Gaiba

Rejoinder: A Permanent Citizens’ Assembly is not a Magic Wand for Europe. But… , by Kalypso Nicolaidis

Kalypso Nicolaidis (European University Institute)

Once again, the European Parliamentary elections taking place in June 2024 have produced democratic angst: do citizens care at all? Will more than half of the European electorate even bother to vote? Will we witness another series of parallel national campaigns? Will a new European Parliament reflect both greater polarisation in Europe and the growth of extreme right representation? Ultimately, these questions boil down to one: do Europeans feel represented by their members of European Parliament – or for that matter by EU institutions in general?

Alas no. Or at least not enough. But there is a silver lining: Our current democratic predicaments offer opportunities for change and for representative democracy to re-invent itself, i.e., the ways citizens, representatives and other actors interact. The challenge is to re-organise democratic life in a social, political, technological and economic context that will never again be the one that prevailed at the 18th-century birth of parliamentary governments. In the era of unfiltered web-democracy we must radically bolster the sense of ‘democratic ownership’ of the EU’s institutions by its citizens.

I will argue that such a sense of ownership can be enhanced through a radical institutional innovation: the introduction of a permanent European Assembly of randomly selected people into Europe’s political landscape. Randomly selected Citizens’ Assemblies (CA) have proliferated around the world in the last two decades mostly at the local level – a trend labelled by the OECD as the deliberative wave. A few of these have become permanent, yet there is no such permanent assembly transnationally. Such a European Citizens’ Assembly (ECA) would not be sitting ‘up there’ in Brussels but be an itinerant body, travelling around Europe and its peripheries, meeting with local actors in multiple configurations that would change over time, with frequent rotation of its members. It would be embedded in a pan-European participatory eco-system that it would also help to bring into being. Call this a leap of faith, but I believe that if citizens can literally see power diffused, they might start to believe they own a share in it.

I am currently campaigning for such an assembly along with others who have set sail under the banner of the Democratic Odyssey project and its initial blueprint. The beauty of the project is that it has lent itself to academic activism: testing one’s ideas by putting them into practice (through a ‘proof of concept’) and revising them as they fail or succeed. Here I would like to take a step back in the spirit of the GLOBALCIT forum by soliciting pro-and-con arguments linked to competing conceptions of citizenship and democracy.

Before I proceed, let me put my cards on the table. This proposal does not rest on a comparative claim as can be found in the vast historical and theoretical scholarship on the respective merits of selection by election vs by lot, a debate brilliantly re-invigorated in our times by the likes of Dahl (1989) and Manin (1997) whose views were far less univocal than that of those who seek to appropriate them today. I do not argue for replacing elections by sortition (as do Guerrero, 2014; Landemore, 2020; for a discussion, see also Owen and Smith, 2018) and share many of the criticisms that have focused on the risks associated with denying the import of politics, parties and organised civil society. But neither do I believe that an ECA should simply be a subordinate body, a mere advisor or faire-valoir for the EP. Instead of throwing out the baby with the bathwater of ‘lottocracy’ (Rummens and Ginnens, 2023; Umbers, 2021; Lafont, 2020), the proposal turns on the idea of complementarity and synergies in order to develop a holistic approach for the EU that combines the best of democratic models by supplementing the EP with an ECA. In short, its value rests above all on its idiosyncratic features (transnationality and permanency) and on its experimental character.

I start by making the case for such an assembly, along its three features, namely, the value of holistic democracy, the challenge of transnational democracy and the promise of permanence. I then move on to offer a heuristic for our discussion along three contested dimensions of democratic legitimacy: popular sovereignty, democratic governance, and civic culture. Each of these is associated with a different rationale for a transnational CA, namely equal representation, integrity, and epistemic diversity. On each dimension I open up the debate to what I consider some of the most difficult questions with a view to making the proposal conditional on addressing potential pitfalls. I will conclude with some reflections on the process of co-creation in the shadow of alternative imaginaries.

The Case for a Permanent European Citizens’ Assembly

The story has been told how, in the 18th century second democratic transformation (Dahl, 1989), political elites prevented the re-birth of ancient practices of sortition in order to limit access to power in the incipient state and to adjacent property rights (De Djin, 2020). Representative democracy has been riddled since the beginning with deep conflicts regarding the appropriate configuration of power in societies aspiring to deliver equal citizenship.

Yet, against the backdrop of increasingly complex state-society relations in the contemporary era, many will argue that representative democracy has been uniquely successful in balancing the dual goals of incorporating citizens’ will, on the one hand, and expertise for efficient policy making, on the other. Today, however, the balance is deeply under strain. I will not rehearse here the diagnosis of democratic dissonance between our system of representation and the interests and aspirations of ordinary people. Representative democracy is being criticised for not being inclusive, responsive or accountable enough and, at the same time, for being too responsive to short-term popular preferences. Out-of-touch elites are pitted against populists, expert knowledge against opinion polls and social media. No wonder populist leaders have emerged to exploit this persistent social anger against institutions.

Thus we have woken up from what Americans used to call the ‘dream of full representation’, a system that was born for a society that no longer exists, where cross-cutting social cleavages could coalesce into temporary aggregations of interest and political coalitions. What we witness instead today is polarised pluralism, with infinite numbers of radically heterogeneous groups, often isolated from each other and unable to connect. Even if political classes had not appropriated politics, todays’ parliaments and governments cannot pretend to represent the whole of society, nor to offer solid resilience against populist and technocratic capture. This state of affairs seem to be compounded at the European level. And so, in short, my proposal rests on three pillars: a holistic approach, transnationalism, and permanency.

The case for holistic democracy

Most importantly, when we speak of citizen or peoples’ assemblies, we need to stress that they rest on combining three crucial ingredients, namely sortition, deliberation and rotation. Each of these plays a key but different role in their legitimacy. In its simplest form, the ECA proposal can be traced back to the ‘sortition movement’ initiated by James Fishkin (1993) who sought to reassert the importance of Habermasian deliberation in our quest for political equality in the making of collective choices, holding up mini-publics as an alternative to the distortions of opinion polls. Since then, the deliberative wave has given rise to scores of conceptual and empirical debates and refinements, and such assemblies have become the symbol of democracy between and beyond elections (Van Reybrouck, 2018).

At the heart of it all lies the injunction to rethink the idea of ‘representative democracy’ by questioning that the delegation of power to political representatives in a legislature and executive is the only form of re-presenting citizens. This leaves us with the need to reinvent the meaning of re-presentation as the many ways in which citizens can be made ‘present’ in the political sphere. If democratic representation can take many interconnected forms, selecting the members of an assembly by lot simply contributes to representing society as a whole.

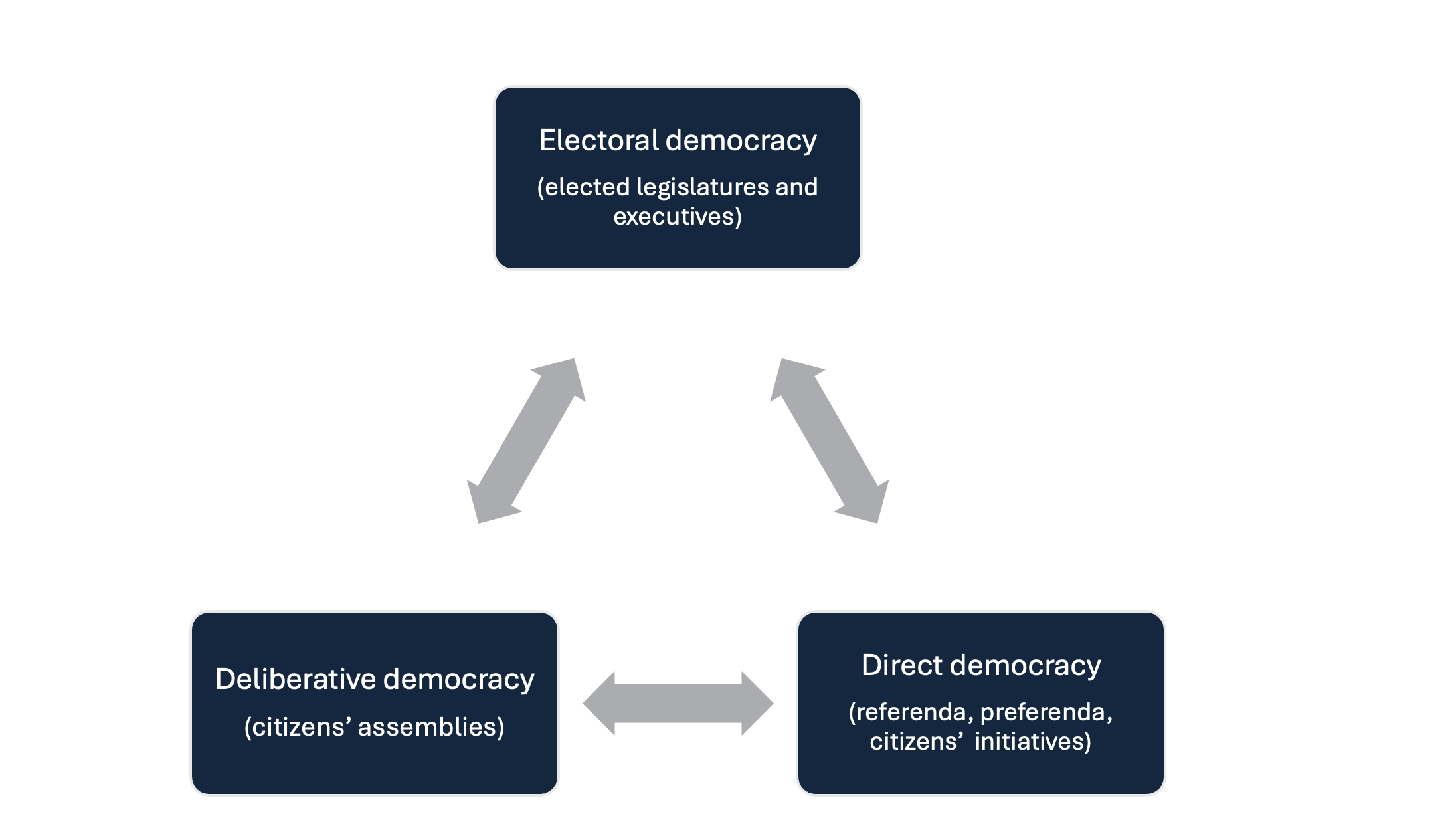

To cut a long story short, the proposal builds on the many ways in which the three logics of representation (electoral, deliberative and direct) and sources of legitimacy can be reconciled and synergised, as they indeed have been in countless experiments, starting with the streams of democratic reforms in Athens in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, from Clisthenes to Pericles.

Only sociologically are these three fundamental forms of democracy alternatives to each other. Elected representatives are often wary of deliberative forms of democracy that they feel might usurp some of their legitimacy or dilute their own control over the levers of power. And advocates of direct democracy fear that deliberative approaches might serve as fig-leaves for citizen participation put forth by those who want to do away with direct democracy altogether.

And yet, when it comes to democratic practices, it would be absurd to do away with any one of these three forms of democracy or diminish their distinct appeal. Instead, if power sharing is effectively to happen, democracy needs to flourish in all its forms at a time where the complexity of governance, regulation and social control has been pushing societies in the opposite direction, namely towards centralisation and monopolisation of control by a few at the expense of the many.

The three fundamental modes of electoral, direct and deliberative democracy are not alternatives to each other. As Hannah Arendt (1958) argued, power is not a zero-sum game. Creating a new (polycentric) centre of power in the EU would likely increase its legitimacy as a whole and, therefore, the legitimacy of the EU itself. It is the combination of these three forms of power and representation that I term ‘holistic democracy’. This view is in keeping with the ‘systemic turn’ in democratic theory, which takes democracy as a unified ideal, not as attached to a specific model, but as a set of practices (Dahl, 1989) that can in various combinations contribute to the democratic character of a polity.

Transnationalism in theory: Towards a demoicratic polity

Many will argue that CAs may make sense at the local level, even possibly at the national level, as we have witnessed in Iceland (2010), Ireland (2016) or France (2019/2020), but why is it desirable to up the ante by promoting them at the supranational level?

Arguably, the limits of electoral democracy are even stronger beyond the state, where directly elected MEPs may complement the indirect legitimacy of government councils but where such directness is not felt by the average voter. The lens of demoicratic theory (Nicolaïdis, 2013; Nicolaïdis and Liebert, 2023) in particular serves to emphasise the horizontal quality of the EU, a polity of multiple distinct but interdependent peoples committed to the mutual opening of their respective democracies. The point of a transnationalism, as opposed to nationalism and supranationalism, is less to deny or debate the existence of an elusive European demos than to elevate horizontality from a positive concept describing the nature of international or European cooperation to a normative one conveying the ideal of ‘ever closer’ mutual commitment between imagined peoples (Nicolaidis 2023) short of modern nation-state-building (Tilly, 2007). Crucially, such horizontality cannot be operationalised without deepening the direct links between European citizens themselves, which in turn requires radical democratic innovations to regulate the joint democratic government of inescapably different, yet also inescapably interdependent demoi (Ronzoni, 2017).

In short, demoicratic citizenship shifts the spotlight from the vertical focus on domestic accountability of liberal theories to horizontal accountability among demoi, among citizens themselves, taking transnational cooperative entanglements all the way down to the citizens, thus translating the idea of transnationalism into translocalism. As leaders balance their respective democratic mandates, publics must demand cognitive tools for engaging in transnational societal empathy and establishing a form of joint and equal control over the conditions that allow their reciprocal non-domination through institutional and legal safeguards at the (EU) centre.

Demoicratic agency is therefore not only exercised simultaneously through the dual routes of national and EU citizenship (Scherz and Welger, 2015) but also through the various channels of democracy from below, empowering both formal and informal civil society to make good on the Lisbon Treaty’s provision on participatory democracy (Liebert, Gattig and Evas, 2016). This involves enhancing formal mechanisms that allow demoi more effectively to borrow from one another and interconnect their different parliamentary, political party and electoral systems. GLOBALCIT has debated in the past how such an agenda would best be served by introducing transnational party candidate lists for European elections, by extending mobile EU citizens’ voting rights to national elections in their host countries and by extending the local franchise to third-country nationals.

But in this panoply, only participatory and deliberative democracy offers the possibility to connect nationals through a mechanism for mediating political contestation in different political and social fields of action. A demoicratic ethos explores a ‘right to participate and deliberate’ jointly with citizens from other states, beyond traditional models of representative democracy that cannot achieve direct democratic interaction and debate across national or metropolitan polities and citizens in Europe.

Transnationalism in practice: Citizen participation between elections is the new EU mantra…

It is noteworthy then that such an ethos has started to be put in practice by a plurality of EU actors, bureaucrats or politicians, as they realise that the EU’s legitimacy deficit might call for an even greater emphasis on citizen participation than in the member states – to counter democratic disaffection and the fragmentation of the European public sphere, to seek legitimacy beyond voting and other traditional rights associated with European citizenship.

With the Treaty of Lisbon (2008), EU citizens acquire multiple participatory instruments (in addition to the right to petition the EP inherited from the Maastricht Treaty) – from the European Commission’s public online consultation and Citizens’ Dialogues, via the role of the European Ombudsman as an advocate for the public vis-à-vis the EU institutions, to the European Citizen’s Initiative (ECI).

But while these mechanisms are broadly welcome, they have, unfortunately, remained too timid and largely ineffective in bolstering bottom-up participation, involving as they do experts and organised interest groups rather than ordinary citizens. They don’t encourage debates on non-experts’ policy preferences and are applied too often at the discretion of the political elites to justify pre-existing policy decisions. In short, they feel more like consultative mechanisms than significant democratic innovations.

To many of us, the introduction of so-called Citizens’ Panels, a new tool for citizens’ participation during the 2021-2022 Conference on the Future of Europe (CoFE), which was sponsored by the three main EU institutions, offered an exciting new promise (EuroPolis, a first transnational EU deliberative experiment was organised before the 2009 European Parliament elections). Four panels made up of 200 randomly selected citizens from all 27 Member States and reflecting the EU’s diversity issued recommendations that are now making their way through Brussels’ decision-making machine.

Here was a demoicratic EU, surfing on the deliberative wave and doing so transnationally, a first in the recent history of the revival of citizens’ assemblies around the world. In the first half of 2023, three new Citizens’ Panels were launched by the Commission (on food waste, virtual worlds, and learning mobility), each comprised of 150 people, which in turn also issued recommendations on their assigned topics. Two more are taking place in spring 2024, one on energy efficiency and the other on countering hatred.

Optimists consider such a deliberative moment a turning point. At least from a political sociology standpoint, there are good reasons to hope that introducing European Citizens’ Panels in the EU’s modus operandi makes them part of a new dynamic that is likely to persist as more European civil servants are progressively converted to their charm. They show that transnational deliberative processes can be effective in enhancing the kind of mutual knowledge and entanglement called for by a sustainable demoicracy (Alemanno and Nicolaïdis, 2021). The CoFE has opened a window of opportunity for reflection on new kinds of political agency and interaction between citizens, political elites and bureaucracies to take the deliberative wave, which has so far reached only the local and national arenas (Chwalisz, 2019), to the supranational level as a crucial way of managing democratic interdependence.

But even if this were the case, how can we speak of a democratic revival through citizen engagement if the CoFE that was supposed to kickstart it has been largely ignored by the wider public? If none of the choices made along the way, from the composition of the assembly to modes of sortition, to choices of topic and types of facilitation were transparent and democratic?

Above all, the panels failed to reach the wider public because they were largely insulated from ongoing political dynamics (e.g. in national parliaments, the media, social movements). They resembled mega focus groups rather than ‘the people’ in action. The stakes and their impact on actual policies remained opaque, as noted by citizens themselves in a letter to the EP’s petition committee.

Moreover, mediating actors (political parties, trade unions, civil society organisations) have only been involved very lightly, which will please purists of deliberative democracy but not those who hold a more holistic view of politics and policymaking in the EU. This remains a process of ‘technocratic democratisation’, or ‘democracy without politics’, where the consultative logic still prevails over the democratic alternative.

In this context, can the European Parliament not offer its own path to combining modes of democracy? It could play a leading role as a standard bearer for strong and more open democratic standards while offering sufficient resources for citizen participation processes and a non-bureaucratic source of legitimacy to confer the type of authority necessary to ground rule making and compliance.

…but a permanent Citizens’ Assembly would do a better job

Even while many would agree that Europe needs more than ad-hoc panels, the idea of a new permanent body for the EU meets with much resistance. Permanent CAs may make sense at the local level, in cities like Paris and Brussels, objectors argue, but why is it desirable to add yet another institution to the already very complex EU edifice as this proposal, and others argue? Let me spell out five reasons.

Continuity. The term ‘permanence’ can be misunderstood. It does not mean that the assembly would be permanently sitting or that its members would hold their mandates for a long time. On the contrary, the ongoing nature of the ECA’s existence will be combined with intermittence through rotating membership (of a few months), a feature which has nearly always characterised bodies selected by lottery in democratic and republican history. Members would meet intermittently and in different places. Nevertheless, such a standing body would become a genuine fixture of the EU institutional landscape, and its stature would be continuous as institutions are meant to be, with a privileged relation to the EP.

Independence. A permanent CA would escape the vagaries of the political cycle. It would avoid falling prey to arbitrariness and cherry-picking as to when and how citizens are convened to form a temporary assembly (or panels for the Commission). As an independent space within the EU institutional structure it would be well placed not only to provide policy input as do the current panels, but could become a source of sunlight shining onto the whole EU edifice – an open monitoring body whose vigilance could enhance the legitimacy of other EU institutions, including the EP. And its independence would be sustained through its own budget. While power cannot just melt in deliberation through the force of argument, institutional staying power can help mitigate power asymmetries.

Learning. Permanence would also correct for one of the drawbacks of ad-hoc assemblies namely the lack of knowledge consolidation, by promoting collective learning over time and refining from experience the way the assembly operates by collecting best practices. Its translocal character would allow for what is sometimes referred to as side-scaling and thus mutual learning across political systems. The learning dynamic through different iteration would not only benefit facilitators but the citizens themselves.

Embeddedness. Permanence would allow the ECA to become more embedded over time. Within EU institutions, both the Commission and the EU would draw its Citizens’ Panels from the ECA membership. It would also be able to develop relations with national parliaments, a crucial dimension of embeddedness. At the same time, its permanency will facilitate the ongoing involvement of civil society as interlocutors, collaborators or counter power. This in turn would empower advocates of citizen engagement within EU institutions in a virtuous circle of connected political spheres.

Publicness and social imagination. Finally, by existing as a standing body labelled ‘assembly’ rather than the more obscure term ‘panel,’ this body would be public in the proper sense, visibly part of the institutional landscape (with or without Treaty change). Permanence would allow it to acquire a status understood and valued by the citizenry as citizenship in action, while the very label and look and feel of the assembly would hopefully appeal to their democratic imagination. There would be a story to tell about the long march of democratic progress, a new way to enlarge the franchise ushered by the third democratic transformation, however tentatively (Nicolaidis, 2024). In this way, the ECA would be a tool for systemic change, not only a footnote to electoral democracy. By giving effect to popular power in a non-ephemeral way at the EU level (Field, 2020), it might even convey the message that the EU is becoming more democratic than its member states. And beyond the EU, it could strengthen the EU’s claim as a global norm-setter on new democracy, adding to its growing clout on data protection and the governance of digital platforms, thus strengthening its ability to support citizens fighting autocratic control.

Embedding the ECA in the EU’s institutional landscape and public spheres

How then do we proceed to assess this proposal? Let me now offer a methodological heuristic and conceptual framework to organise our discussion.

First I suggest three main criteria. These are standard dimensions of democratic legitimacy, namely popular sovereignty, participatory governance, and civic culture or ownership, which correspond to different problematiques and sometimes even disciplinary commitments, but which are arguably complementary (Szulecki, 2018). This tripartite division roughly corresponds to input, throughput and output legitimacy.

Second, I further suggest that each of these criteria allows to highlight a different argument or rationale typically offered regarding the value of citizens assemblies, and I ask how each of these rationales transfers to the transnational/permanent attributes of the ECA.

Third, however strong these arguments, the idea of an ECA has faced considerable pushback. I believe that objections are best addressed by thinking through the relationship between the ECA and the EU’s institutions, most importantly its parliament and asking in particular under what conditions the ECA’s relation to the EP could be synergetic rather than one of subordination or substitution.

Popular Sovereignty: The argument from equal representation

If popular sovereignty were to mean that all political power must be vested in the people, CAs in general and a permanent ECA in particular would not remedy the exclusion of the vast majority of citizens from the circle of rulers. If this is inevitable, traditional electoral representation has unique advantages of creating an explicit mandate for representing the will of voters under the banner of political equality by combining one person/one vote with the progressive expansion of the franchise across time.

An assembly created through random selection can claim to supplement such equal representation on two counts, through what Manin calls “egalité de probabilité” and through alternative ways of effectively widening the franchise. By mirroring the general population in statistical proportion, it creates another kind of proxy than the EP for popular representation. As it is practised today, sortition usually involves two stages. At a first stage, a lottery takes place to invite people to become assembly members from a pool of randomly drawn citizens. At a second stage, a process of ‘stratification’ is applied amongst all those who respond positively to this first invitation in order to ensure broad representativeness. Borrowing from techniques developed for opinion polls, potential self-selection biases are corrected to create the final assembly using criteria such as gender, age, education, income, race, geography, based on known distributions of these criteria in the general population.

Moving from the aggregate assembly which is statistically or descriptively supposed to be representative, to the individual members, we can add an affective or identification dimension to ‘representativeness’, as research shows (with caveats) that the public tends to see these members as ‘people like us’ – in contrast with the EP, where the social gap between representatives and electorates is much more pronounced.

But can a few hundred citizens selected by lottery ‘represent’ 500 million citizens across 27 or more countries? They can, at least to the extent that the selection process is communicated and explained to the broader public in a way that is radically transparent, through what I call ‘a pedagogy of sortition’. By contrast, electoral candidates in EP elections are themselves chosen non-transparently by political parties with vertical chains of delegation that are increasingly remote from individual citizens.

Over time, the pedagogy of sortition can teach the wider public that the core ethos of randomness is equal chance. If explained well, in fun and accessible ways, sortition allows people from all walks of life to perceive that they have an equal chance of being selected (even if with a very small likelihood) whereas they would not stand a chance in the traditional electoral system monopolised by professional politicians, shaped by the oligarchic nature of political parties and plagued by extremely high barriers to entry, especially at the EU level. The argument for enhancing democratic equality is all the more important in an EU where some states and therefore their citizens are perceived as more equal than others. In an ECA, a German worker or a Latvian teacher can feel closer to respectively a Spanish worker or an Irish teacher than to their co-nationals. And collectively, they can claim to mirror the concerns and hopes of broader sways of citizens across borders.

But who is us? Composition, criteria and pools

One first difficult conversation has to do with who decides how a representative sample of a transnational public is designed. Analysts of sortition have recently sought to develop what they call ‘fair algorithms‘ for selecting citizens’ assemblies with probabilities as close to equal for any individual within a polity as mathematically possible, creating metrics of ‘closeness to equality’.

Democratic progress has traditionally been equated with the expansion of citizenship status, the franchise and electoral rights, the foci of GLOBALCIT. Citizenship thus became a byword for ‘full representation’ in electoral democracy, an increasingly impossible equation as societies grow and become more diverse and polarised. Moreover, progress towards inclusiveness in processes like EP elections has come to a halt both formally and informally, with rising numbers of non-enfranchised migrants from third countries and of abstention among those who have voting rights.

Here I argue that the ECA’s composition would not be fixed once and for all. As an institutionalised experiment, it could evolve organically in a radically transparent and inclusive manner. Its ultimate ambition would be to stimulate and expand our social imaginary through a process of evolution taking in citizens’ understanding of citizenship and representation and their different conceptions of the public sphere.

Here are some elements:

Let us imagine that the ECA has 300 members (mirroring 300 million European voters), with a third of them renewed every 6 months. The initial pool is drawn from across Europe. A purely random technique is chosen to create the base pool from which willing participants will be extracted by applying criteria that will create a sufficiently diverse assembly.

The criteria chosen to compose the ECA are of course key. A first aspect has to do with the distance between a polling logic that a sample is representative only if it is sufficiently large (several thousand across Europe) and a logic of political representation where deliberation and decisions need to happen within a much smaller assembly. So even if, as with pollsters’ samples, the composition of the assembly needs to match the known socio-demographic composition of the total population, we should still question the most apparently neutral criteria of ascriptive identity and ask who decides which ascription is relevant (if age why not height?). In my view this itself needs to be debated democratically.

Moreover, the question remains on what basis it is legitimate to add weight to underrepresented groups. Arguably, it seems justified to over-represent for instance younger generations, in part to compensate for their weaker presence in the EU (where the average age is 50), in part to acknowledge the agenda-setting function of the assembly. One could even imagine that the EP starts by creating a permanent youth assembly to road-test the idea.

Similarly, the assembly could over-represent small states in the EU, to balance the fact of degressive proportionality in the EP (that is proportional to the population of each member states but with overweighting smaller state). An extreme solution, which I would favour, could include the same number or quota of delegates from each member state (so about 12 per member state).

This also makes it easier to form language groups at the onboarding stage, when citizens who have been selected are first socialised and familiarised into the process and provided with information, which I do not believe would ultimately create national silos. If, for instance, the delegates from 10 member states were replaced every 6 months from instance under the rotation principle, all member state representatives would mingle at some point in time. The criteria could also include sub-criteria of representation for the major regions of Europe, especially regions composed of some member states or parts of these (e.g. Nordic, Baltic or Mediterranean), whose representation would count for all states that they straddle.

Over-representation can also apply in socio-cultural and socio-economic terms, starting with the proposal to over-represent minorities or disadvantaged groups. This would counter-balance the more elitist socio-economic make-up of the EP. So we need to define who belongs to which minority, and ask what kind of capacity building is necessary to make effective the idea that recruited delegates who may not have thought of themselves as citizens with a legitimate voice can be helped to do so. To be sure, members recruited to the assembly on the basis of a minority criterion might think that they need to represent only the interests of that minority rather than deliberate about the common good. This risk ought to be addressed explicitly in the early socialisation phase. But in the end, how do we deal with the fact that people with, say, lower levels of education simply refuse to participate remains an open and tough question.

Even more drastic approaches might be necessary to balance the ideological self-selection bias of the Assembly. Those who say yes to the initial invitation are obviously likely to care more about Europe, thus generating an over-integrative assembly. At least the EP has a plurality of ‘anti-system’ delegates. Some scholars have therefore defended a selection method that would include behavioural or attitudinal criteria, perhaps through a more complex preference tableau than simply asking people if they are Europhiles or Eurosceptics. Since random sampling is anyhow not blind sampling when stratified, this would not in my view undermine descriptive representation legitimacy in a political rather than simply sociological sense.

Regarding inclusiveness, many in the NGO sector advocate the inclusion of long-term resident third country nationals who cannot vote in EP elections. I would strongly advocate such inclusion which would partially compensate for the limitations of the EP franchise and the power of member states to determine EU citizens under their own nationality laws. The selection pool for the ECA could thus provide a contrasting inclusive identity for a wider residence-based EU demos. The co-existence of this inclusive deliberative demos with a citizenship-based electoral demos for the EP would highlight the fluidity of membership boundaries in the European polity in a productive way and perhaps facilitate migrants’ political integration.

Another route to inclusion would not add new criteria for the second stage of selection from a single pool but create several separate pools from which to draw different configurations of the assembly. To the pools of member states’ nationals and residents, other kinds of pools can be added on an ad-hoc but principled basis, such as EU citizens living in third countries or even citizens from the rest of the world if the topic called for it (e.g. agriculture, trade policy). Democratic Odyssey activists have also proposed to create a separate pool of ‘veteran citizens’ (participants in earlier citizens’ assemblies) in later assemblies.

To reflect and convey its itinerant, local, but also translocal character, the assembly could consist in the merger of different pools. Thus, in addition to a purely transnational pool (with all the criteria discussed above), there could be a pool of local citizens that would join the assembly for its meetings in a specific city or region and remain involved remotely for the next six months as the Assembly moves on to the next city.

Finally, beyond criteria or separate pools, the ECA can rely on a third path to inclusion and take on a mixed character, combining ‘ordinary citizens’, of the randomly selected kind, with politicians to enhance political buy-in, as well as representatives of civil society organisations to enhance societal and activist buy-in. To be sure, the inclusion of non-impartial actors with their political agendas will increase the influence of both locally grounded and transnationally active citizens, which is not a given in the EP context.

This third path to inclusion could also introduce altogether new logics of representation – an ECA finding new creative ways to represent the absents, including future generations and non-humans. This is one of the key challenges when dealing with environmental and biodiversity decision-making but is also relevant far beyond these issues. Inclusiveness here takes us all the way to a new kind of longue durée ‘multispecies democracies’. These absents can be rivers, oceans, forests, species affected by the actions of governments and other actors that do not take their needs or rights into consideration without necessitating concurrent responsibilities. This is about imagining multi-species justice encounters, recovering the ability to create new worlds, within a relationship that the Maori refer to as genealogical. Such a radical enlargement of citizenship can burst assumptions about who or what matters given the power structures of current worlds. The assembly can include spokespersons, or rather ‘guardians’, as in the cases of rivers granted legal in courts from Australia to India to New Zealand. More creative ways to do so include more interpretative methods through the inclusion of civic artists who literally ‘interpret’ these other worlds, or life scientists who bring in stories about other species’ modes of collective action.

Taking into account this array of proposals, the standing ECA can represent Europe’s fluid and overlapping demoi in a quite different way from the familiar and traditional EP model and would allow MEPs themselves to explore new ways of ‘representing’ as they interact with these demoi.

Democratic Governance: The argument from integrity

The second group of arguments concern the processes of democratic governance, or what some refer to as open government. Arguably, the ECA could serve as an ally for those MEPs who seek to furthermore open governance in the EU.

It is commonly argued that sortition addresses what is perhaps the most universal threat to the democratic character of governance, namely the risk of corruption and capture, the appropriation of the commons by the few. Preserving the idea of the common good that collective decision making is supposed to serve is especially important if we emphasise not only procedural but also substantive understandings of democracy. As I and others have argued in a 2023 CEPS report, risks of formal and informal state capture abound in the public administrations of European countries (and candidate countries in particular). These include the politicisation of the civil service, nepotism in the distribution of public posts, budgetary capture by special interests, and generalised corruption at the highest level of government. An ECA could constitute a democratic tool par excellence to reduce social distinction in the distribution of power in Europe and to prevent power from being monopolised by a group of professionals (political, bureaucratic, judicial, or expert). At EU level, lobbies hold great sway and corruption scandals like the EP’s Qatar gate have further increased citizens’ distrust.

Moreover, in taking a systemic approach to considering an ecosystem of new institutions an ECA can also serve dedicated functions of oversight and monitoring, which could be integrated into the management of regulatory, certifying, and supervising agencies and in the distribution of EU funds. If EU institutions rightly allow for the expression of national interests and the agonistic confrontation of societal values, a system of CAs can help overcome the deadlocks to which such confrontations give rise. These considerations are especially relevant in responding to authoritarian challenges to democracy. A powerful and impactful ECA could greatly contribute to the EU’s much needed democratic resilience.

I prefer the term integrity to impartiality here, as it is hard to imagine impartial citizens uninfluenced by prior political or cultural beliefs, including through exposition of opposing views in the assembly itself. In this sense, this proposal does not rest on criticising members of political parties for being partisan or loyal to a set of ideas. Integrity is not a quality imputed to the intrinsic nature of our randomly selected citizen but to the context of quick rotation, leaving no time and incentives to entrench corrupt practices (Mungiu-Puppidi, 2023). They have no political career nor party interests to defend. Special interests, lobbies, and factions do not have enough time to capture them. They are more immune to corrupting influences than career officials or politicians. Hence, for at least partially disconnecting politics from power, rotation is as much a key to anti-corruption as sortition. And thus the ECA would become a likely ally for all MEPs seeking to differentiate themselves for their peers who have proved highly vulnerable to capture by specific interest groups and lobbies. The ECA therefore would affect power balance within the EP.

Integrity matters all the more since the EU, as the rest of the world, is undergoing a deep transition which impacts extremely powerful players, namely the fossil fuel industry, who have the means to resist the necessary legislative changes. Being more immune from special interests can help in balancing the imperative of social justice (without which transition towards net zero climate emissions will not be legitimate in the eyes of EU citizens) with a realistic understanding of the road that has to be taken (through public hearings of all stakeholders) to fight climate change.

There are many ways how this ECA and its members could connect to other parts of the EU political system and its eco-system of power, influence and decision making. Its mandate could start with contributing to agenda setting for the EU as a force for translation of debates taking part in the EP, while also deliberating on concrete policy issues, discussing successful ECIs, or taking part in a mixed conference or convention. It could also be entrusted with scrutiny-related tasks to monitor the implementation of decisions and ensure good governance and the integrity of the European institutions alongside other bodies such as OLAF and the Ombudsman office. The assembly would cooperate closely and meet with the other three main institutions as well as civil society organisations, political parties, trade unions and other relevant organisations. Arguably, an ECA at the heart of the EU could play a crucial monitoring role in this regard, as part of what I call the ‘democratic panopticon’.

In doing so it would root participation infrastructure at the local level and work through multiple governance approaches to reach national and European structures and become part of a wider participatory turn that gives people confidence that there are multiple ways to bring their opinions forward. Such an open shared infrastructure for participation will rely to some extent on a learning mindset within government administration. This could help spread an ethos of democratic respect throughout the various EU instruments, including democratic control over the spending of EU funds at all level of governance (Nicolaidis, 2023)

But should the ECA be enabled to decide?

There are however serious debates around the pathways to impact, and in particular the binding character of recommendations issued by citizens’ assemblies. Yet what would be the point of following Dahl’s injunction that CAs should not decide and issue binding recommendations, keeping with a purely consultative role as with the current Citizen Panels? To make a difference in the eyes of citizens, an ECA ought to be more than a space to create ‘good European citizens’. It must be a source of authority per se. Otherwise, it risks being perceived as just another tool that elites use to legitimate their policies rather than a tool of diffusion of power.

This does not mean however that the choice we are faced with is binary. The reason invoked not to give assemblies selected by lot a role in decision making has to do with accountability, which is often said to be based on the combination of personal choice on the part of the candidate involved with membership in a political party and standing for election, on the one hand, and the choice of the voters for such candidate, on the other hand. CA members, it is argued, neither choose nor are chosen. But is this argument as solid as Dahl or others would have it? I would argue that acceptance of membership in an ECA is also voluntary and calls for a more complex sense of accountability, namely collective accountability as an assembly, even if members cannot be held accountable individually.

But there is a better reason to resist calls for ‘bindingness’ of ECA decisions. The EU is a system of shared and multi-level governance (this is for law-making of course, not executive decisions by the European Council or the EU’s financial bodies that warrant a separate treatment) in which no single institution can issue binding edicts, hence the complex co-decision procedure between EP and Council. These processes need to remain tied to the electorate’s consent, however tenuous the connection.

More promising and creative is the option of linking the ECA to direct democracy instruments in cooperation with the EP. For theorists who seek to ground their argument in political history, it is worth remembering that if the randomly selected council (boule) did not take decisions in Ancient Athens, it did frame them for the popular assembly (ecclesia) akin to open air referenda. Here, we can imagine that for instance the ECA produces an ECI, which might then go to the EP to be turned into a legislative proposal if the EP were to acquire a right of initiative. The ECA could also produce directly questions for an EU referendum, or better multiple choice preferenda. The link with direct democracy could also happen upstream with the ECA taking on the agenda proposed by a winning ECI. (For a stylized typology of the different ways in which the ECA can be combined with the EP and referenda, see Berg and Nicolaidis, forthcoming).

If these options seem too radical, let us not forget that the boule and the ecclesia could not avail themselves of innovative digital technologies as discussed in the next section. We would, of course, need to discuss the conditions of possibility for such a radical empowerment of the ECA, including the technologies of constraint it would be subject to, from the rule of law to various bureaucratic safeguards.

Civic Culture: The argument from epistemic democracy

A third question to examine concerns the broader impact of an ECA. My hope is that the democratic respect demonstrated by its existence and performance would prove contagious and contribute to fostering a sense of civic ownership and a more democratic civic culture throughout the EU even in the absence of a unified public sphere.

This in turn takes us back to the deliberative quality of the ECA, which in its diversity can embody ‘epistemic democracy’, or epistemic diversity as the expression of radically different types of world views connected to different cultures and languages, by confronting them under quasi-ideal circumstances: high-quality deliberation and moderation, wide-ranging information from all sides, contradictory viewpoints, general assembly sessions alternating with small group discussions, inclusive and reciprocal listening, as well as shared decision-making by consensus.

Under these conditions, a permanent CA will not only enhance the legitimacy of EU institutions but also the quality of its policymaking, including by combating disinformation as part of a broader institutional framework dedicated to dealing with citizens’ ‘right to know’ and ‘right to know how to know’ (Alemanno & Nicolaidis, 2022; Palomo Hernandez, forthcoming). In ancient democracy citizens had incentives to keep themselves adequately informed because they could be selected in the political sortition at any time. This seems much less relevant today (Abbas & Sintomer, 2021). But the negative argument that traditional representative democracy provides incentives for manipulation and control of information flows by the elites has not lost its relevance (Manin, 1997).

Even if we were to buy the neo-Platonic argument by Jason Brennan and others that ordinary citizens do not have the expertise required for good government, random selection combined with frequent rotation ensures that the many are wiser than the few, whatever nuances one may attach to the ‘wisdom of the crowds’. New forms of citizen inclusion (not only CAs and citizen juries but also informal civil society, social entrepreneurship, and other non-electoral forms of participation) offer crucial ways of linking established sources of expertise with new ways of harnessing collective intelligence, including social media and AI. As brilliantly documented by the Collective Intelligence Project, innovations offer the opportunity of enhancing all types of democratic representation and effective governing and more broadly rethinking ascribed claims to expertise. Civic technologists are developing tech-enhanced tools for value elicitation to aggregate, understand, and incorporate the conflicting values of overlapping groups of people as a foundation for complex decision making, such as sense-makers quadratic voting, quadratic funding or deliberative tools like Pol.is. used in Taiwan and elsewhere, Barcelona’s Decidim approach, or platforms like Participatory Value Evaluation tool (PVE), which helps lay out the policy implications and long term consequences of policy preferences to manage large-scale deliberation leading to recommendation. These can create platform assemblies to generate decisions, that can even be managed by AI boards.

Instead of merely watching these dynamics, the EP could partake in them in tandem with the experimental space offered by the ECA and thus connect its own debates with the wider public, especially when these debates involve difficult trade-offs and choices that need to be debated in the open.

Arguably, this epistemic advantage of the ECA would be even stronger because its transnational nature could make it over time the visible incarnation of the EU as a ‘community of translation’ across political cultures and beyond politics, exploring ways to overcome linguistic barriers between ordinary people where diversity is radically magnified, and where learning systems vary as do cognitive and collective biases. Europe is more likely to make good on the demoicratic promise if it sets up ways of channelling the life wisdom, knowledge spheres and expertise of a broader range of individuals than those self-selected in the political and bureaucratic spheres.

This effect would be all the more precious as a permanent assembly would visibly and publicly serve to counteract insidious polarisation, which even the EP is increasingly succumbing to, by elevating the value of collective compromise and consensus and attracting members to the radical middle allowing for “participation without populism” (Gardels and Berggruen, 2019). In contrast with the evidence that polarisation and elitism reinforce each other, there is empirical indication that individuals participating in CAs reduce their polarisation on the issue they are deliberating on whether we consider issues related to climate, migration, agriculture, or security (Dryzek et al., 2019; Grönlund et al., 2015). In such assemblies, citizens tend to own up more readily to their ambivalence and thus listen to the other side, including across cultural and linguistic barriers where positions can be more easily framed as oppositional.

But how does the ECA connect to a wider European public sphere?

Many have objected that CAs and in particular the argument of epistemic diversity feed into the fantasy that deliberative assemblies can legitimately serve as a proxy for the broader political constituency, by abandoning mass democracy (Chambers, 2009) feeding a kind of deliberative elitism (Moore 2018), and generally overlooking the need for broader citizens engagement (Lafont, 2015). In sum, ‘lottocracy’ constitutes a ‘shortcut’ (Lafont, 2023) which in the end fails to address the quality of participation and deliberation in the broader public sphere that connects civil society with decision making and state apparatus. This is held to be especially true if they assemblies cut across domestic political cultures and nationalised public spheres (Olsen & Trenz, 2015). In this view, there may be scientific value to an ECA as a sealed experiment but that would not count as a democratic exercise. When the idea of ‘self-representation’ feeds into the idea that intermediary actors are obstacles to realising the values of neutrality and consensus, we lose the eminently progressive idea that politics enables the fair redistribution of various goods in highly unequal societies. Ultimately, such a disintermediation narrative could look like deliberative populism, denying the importance of politics and the relevance of struggles that have spearheaded social progress in the long run.

This is perhaps the hardest and most important issue in this story. How can the ECA be more than a form of cooptation and ‘citizen-washing’ and contribute to transforming Europe’s civic culture and citizens’ sense of civic ownership of their institutions?

For one, an assembly that cuts across national controversies will need even greater agonistic confrontations than the national kind if it is to attract attention. It could do so by choosing topics with high political salience, lending themselves to express disagreement over issues that require making difficult choices between alternatives and thinking through trade-offs between various costs or benefits that cut across borders, as well as overcoming ascriptive profiles (northern vs southern societies, western vs eastern politics). If this is the case, there is a lot to be said for mixed member deliberative fora or ‘democratic coupling’ with politicians included as members sitting side by side with randomly selected citizens, as witnessed in Ireland, Finland, the UK, or Belgium (Harris, Farrell and Suiter, 2023). Procedural safeguards can be taken against the risk of elite domination which could limit the Assembly’s contestatory role, a lesson drawn from the end-game ‘plenaries’ during CoFE. As these configurations have been shown to increase trust in politics, it might be quite attractive for a subsection of the EP to rotate as ‘EP members’ of the Assembly.

Ultimately, as mentioned above, probably the most straightforward way of connecting an ECA to a wider public is to link it to some elements of direct democracy as the Irish case demonstrated where assembly proceedings were followed broadly around the country precisely because they were to lead to referenda on abortion and gay marriage. The point is not that the assembly dramatically changed public opinion, which had already undergone profound social change before, but rather that the difficult debate preceding the vote was filtered by a deliberative ethos.

The ECA needs to go further and engage not only with democratic audiences who listen but with publics who speak on an on-going basis and not only through sporadic highly controversial debates.

Indeed, if the claim that an ECA ought to connect directly with the people is not embedded in a broader narrative it feeds a logic of disintermediation. Such a logic is not only unrealistic but also potentially undesirable, suggesting that an atomised group of individuals ought to bypass formal and informal civil society, les forces vives de la societé whose mission, commitment and expertise is precisely to interfere with the decisions of elected officials between elections. Organised civil society actors will find an ECA irrelevant at best and threatening at worst if it fails to engage with their own campaigns, movements, and civic dialogue. If the ECA is to claim more that the kind of stakeholder consultations conducted by Commission, it will need to cooperate in its agenda-setting with these actors rather than compete with them. In this sense, the relevant complementarity in terms of legitimacy is not between the EP and the ECA but between the EP and the eco-system of connected spaces of direct democracy which the ECA could help support and interconnect.

Debates in the ECA need to be translated to the general public, but translation requires connection and transmission belts. At a minimum, the assembly can ‘take the pulse’ of the broader citizenry through polls. It can do so before, during, and after a debate. But there are also more direct ways to crowdsource input into the assembly, as experimented with by the Icelandic assembly of 2011 (Blokker and Gul, 2023; Gylfason 2013; Popescu and Loveland, 2022), or the Irish assemblies, which used public submissions with various actors sending their ideas for consideration. The Estonian People’s Assembly (2013) gathered inputs from wider society through an online platform (Jonsson, 2015).

In the same vein, a media partnership supporting, following, and indeed debating controversial debates can help. Special attention must be paid here to so-called ‘solution journalism’, i.e., reports on how people solve problems. Such journalists, or also influencers and other kinds of informal activists, could be embedded in the assembly (Milanese et. al., 2020). Connection through peers and social media that can generate content on the spot matters most for young people. We also need to explore more creative and interactive ways of connecting, from collaborations with the gaming industry to various experimental methods of communication appealing to a broader public inspired by sport, music and festival gathering, the Eurovision or political talk shows (Fricker et. al., 2013).

More actively, the ECA could create interface channels between the assembly and the broader public through platforms and actors like NGOs or civil society organisations that have particular target audiences.

The travelling nature of the proposed ECA meeting in a polycentric way around Europe would help to reach beyond the ‘usual suspects’ connecting cities through a kind of deliberative relay. Such a genuinely translocal dynamic could thus shine a light onto local places that would be shared in the social media space while adding a European dimension to local deliberative processes. And as a mostly young assembly, it can create or encourage European Woodstocks of Politics (Nicolaidis, 2007, see also the European Movement International or the European Youth Event, EYE). In this process, local and translocal civil society organisations in Europe would also experiment with new ways of connecting with the general public while leveraging networks of cities like Eurocities and connecting with projects like the European capital of democracy that could host the assembly.

Regarding the proceedings of the ECA itself, randomly selected citizens could be encouraged to engage with their local communities in preparation for and during their services, turning the table on who is to be considered as the source of expert knowledge. They would present their findings in the assembly’s plenary from both their shared life experience and onboarding meetings in their local communities, while the experts would respond and ask further questions. This dynamic could encourage other citizen to take part directly or in their own spheres in the relevant deliberations.

Ultimately, the bet here is that by a kind of contagious exemplarity and porous boundaries, the ECA will enable deliberative opening beyond both national closure and the ‘Brussels bubble’ between individuals with layered identities – local, regional, national, and transnational ones –where it could achieve impact in a broad array of settings beyond sortition. Arguably, since an ECA is meant to augment participation beyond the self-selection of electoral candidates, it could spearhead such non-elitist participation elsewhere. As itself a school of democracy, it could galvanise a civic culture in schools, firms and neighbourhoods across the continent, contributing to a growing participatory ecosystem. If a European civic culture were to emerge, quipped The Economist “it might conclude that it would rather the union adapts its institutions to its people, and not its people to its institutions” (1 May, 2024).

Conclusion: Contrasting imaginaries and academic debate as co-creation

I have suggested ways in which a permanent European Peoples’ Assembly in the EU could redefine the contours of European citizenship and offered a holistic model of democracy in which such an ECA would work in synergy with the EP.

I would like to end with one further thought, related to the Democratic Odyssey’s theory of change that purports to combine top-down with bottom-up dynamics. Reflecting on the questions raised above and my own very partial attempt to address them, I find that these dynamics correspond to two ideal types, or what Sintomer and Abbas (2021) refer to as the deliberative, antipolitical and radical democracy imaginaries, which are almost impossible to reconcile.

On the top-down side, we find what I have coined as ‘technocratic democratisation’, an anti-political imaginary which celebrates the disintermediation between individuals and the state and, therefore, a direct link between political institutions and the citizenry. As new creative ways allow for an assembly inclusive of otherwise unrepresented or under-represented people, we can create an inclusive alliance between civil servants and ‘the people’. But do we not risk a kind of bureaucratic or corporate populism that hollows out existing political institutions and bodies in the name of an illusionary marriage of deliberation, neutrality and rationality? Does it really make any difference to popular support for democratic institutions if 150 citizens are coopted every six months?

On the bottom-up side, we find, in contrast, variations on more radically political approaches, where the assembly is connected with local public life and transnational movements, embedded within vibrant agonistic struggles. These approaches value political conflict over consensus while seeking to create civil exchanges between highly contested positions. It is not a sealed-off protected sphere, but one political space among others. And it serves to counter authoritarian capture ‘under the radar’ by empowering local democracy through transnational means.

I remain confused on how to bring together these two perspectives through a holistic democratic imaginary so that the various democratic spheres and sites of power enable each other in the quest to reconcile the transformative potential of deliberation with the agonistic nature of politics.

My solace here is that we are not building alone. I cherish the thought that this is a unique opportunity for the co-creation of European democratic theory and practice, among scholars as well as with civil society actors and social movements (Fleuß, 2021). And the thought that, by creating a standing ECA, the EU could serve as a laboratory for a radical transformation of democratic citizenship beyond the state that is relevant globally (Nicolaidis, 2024). What is at stake is democratic stability and resilience in a world where growing numbers of citizens are inclined to support authoritarian forms of government.

The idea of self-government whereby each citizen can imagine herself as being ruled and ruling in turn throughout her life is both the oldest argument in favour of sortition-based political bodies and the hardest to translate in the context of contemporary states and the growing complexity of governing. Yet, imagine the look and feel of our EU polity if citizens throughout the continent were more than just intermittent voters who are only asked to give their opinion once every five years, in 2019, 2024, and next 2029. Imagine that our voices, opinions, and collective intelligence were heard on a permanent basis, rather than on politicians’ whims. In spite of its imperfections, drawbacks and blind spots, let’s give this vision a chance.