Bronwen Manby (European University Institute)

On 13 June 2023, the South African Supreme Court of Appeal found to be unconstitutional the requirement established by the Citizenship Act for adults who voluntarily acquire another citizenship to gain permission to hold dual citizenship from the minister of home affairs, or lose South African citizenship automatically. Those who had lost citizenship under the existing provision were ordered to be deemed to still be South African citizens. Overturning the judgment of the High Court, the Supreme Court accepted the arguments made on behalf of the main opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, that had brought the case.

Regional and global trends

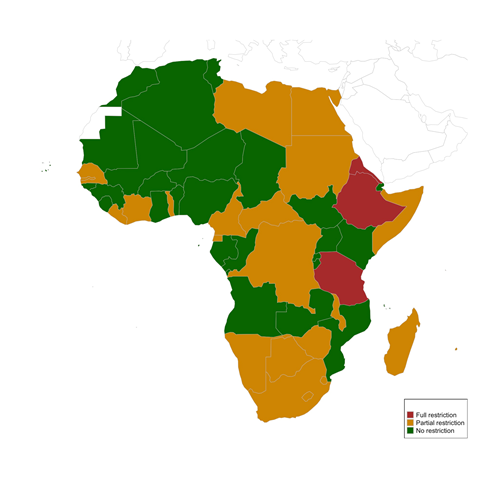

The Supreme Court judgment joins a handful of similar cases across Africa challenging restrictions on holding dual citizenship. While Africa shares the global trend towards tolerance of multiple citizenship, some countries still maintain a partial or total ban. As reflected in Figure 1, drawing on data from the recently updated GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset (and including a partial liberalization in Liberia during 2022), 28 out of 54 countries in Africa (excluding Western Sahara) fully accept dual citizenship in 2023, while 23 states partially restrict dual citizenship. A small number of laws still provide for automatic loss of citizenship if a person acquires or retains another country’s citizenship as an adult; others require a person naturalising to renounce original citizenship; while others require a person to gain permission to hold more than one citizenship. Only three countries (Ethiopia, Eritrea and Tanzania) fully restrict dual citizenship for adults.

Figure 1. Dual citizenship restriction in Africa, 2023

Source: GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset, v2.0, modes: A06b, L05, L06 (incl. 2022 update Liberia)

The South African case illustrates two different sets of principles that arise in these cases where dual citizenship is still partially or fully restricted: first, and most commonly argued, the question of due process; and secondly, and more fundamentally, the impact on human rights, leading to the implication that a substantive right to multiple citizenship should be recognised.

The importance of due process

The Supreme Court focused largely on questions of due process. It set two questions for itself to answer: whether the relevant provision of the Citizenship Act violated the constitutional requirements for ‘rationality’ in the exercise of public power; and whether the provision infringed any right in the Constitutional Bill of Rights and, if so, whether this could be justified by the provisions governing limitation of those rights.

Drawing on the strong constitutional and legislative protections for due process and ‘just administrative action’ in South Africa, and previous jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court interpreting these requirements – as well as arguments put forward by scholars critiquing the High Court decision – the court found against the government on both points. Firstly, the provision in the Citizenship Act was held to be irrational, because it established no legitimate purpose justifying automatic loss of citizenship for those naturalising elsewhere, where dual citizenship is otherwise permitted both for those naturalising in South Africa and for those who are dual citizens from birth. The ‘unbounded’ discretionary powers of the minister to refuse permission for retention of citizenship was ‘a recipe for capricious decision-making’. Secondly, the legislative provision violated the article in the Constitution to the effect that ‘no citizen may be deprived of citizenship’; it overruled the High Court to find that no distinction could be made between automatic ‘loss’ and administrative ‘deprivation’ in this context. The risk of denial of the other rights of citizenship (voting and standing for public office; freedom of movement; freedom of trade, occupation and profession) could not be subject to the unconstrained discretion of the minister.

The South African case joins other recent judicial decisions from around the continent in which dual citizenship has been litigated. In some countries, this litigation mainly works to enforce existing law. In Zimbabwe, for example, the courts have repeatedly been called on to order the Registrar General to issue citizenship documents to those who are citizens by birth and permitted dual citizenship since amendments to the Constitution in 2009 – although the legislation has yet to be updated. In other cases, litigation has played an important role in accelerating law reform. In 2019, the Liberian Supreme Court ruled that the statutory provision for automatic loss of Liberian citizenship in case of acquisition of another citizenship was unconstitutional. The key reasoning of the court – as in South Africa – was based on due process: the automatic loss provision violated constitutional provisions for a hearing before deprivation of any right or privilege. The judgment was followed in 2022 by amendments to the Aliens and Nationality Law to permit dual citizenship in these cases (barring cases where a person is born with two citizenships, a prohibition established by the Constitution itself) as well as to remove gender discrimination in transmission of citizenship to children born abroad. In 2022, a petition was filed in Tanzania, where a complete ban on dual citizenship for adults is still in place, again invoking due process to argue that automatic loss of citizenship violates the constitutional right to be heard before any adverse action is taken against a person.

A human right to dual nationality?

A more radical approach was taken in a 2022 judgment of the High Court in Botswana, home of the famous Unity Dow case in which the Court of Appeal ruled in 1992 that discrimination based on sex in transmission of citizenship was unconstitutional. Ruling in a case brought by Botswanan parents of children born with dual citizenship, the court found to be unconstitutional the legislative provision that would cause their Botswanan citizenship to lapse on reaching majority, unless the other citizenship were renounced. The court held that the prohibition violated the right to family life and a number of other rights, was disproportionate to the claimed public purposes, and discriminatory on grounds of marital status and of origin. (The court was no doubt emboldened by the fact that draft legislation to permit dual citizenship was before parliament – though apparently indefinitely delayed.)

In 2010, Peter Spiro argued that dual nationality should be recognized as a human right, on two grounds: the right to freedom of association, seeing nationality as analogous to membership of a club; and ‘for the perfection of political rights’, since the requirement for renunciation places barriers to political participation in a state where a person has naturalised.

There is no decision of an international treaty body – nor even an authoritative soft-law text – that has moved towards endorsing these views. Although there is no longer a presumption in international law that dual nationality should be avoided – which was the view of the first international codification effort on nationality The Hague Convention of 1930 – there is equally no settled view that it should be permitted. The Council of Europe’s European Convention on Nationality, adopted in 1997, takes a neutral position for adults, although it provides that dual nationality should be permitted for children.

Only the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has moved tentatively towards establishing limits on powers to restrict dual nationality among EU member states, requiring proportionality in rules on automatic loss of nationality, even as it has continued to assert member state discretion. As in most of the African cases, the emphasis of the CJEU has been on due process. Enabled by the national constitution, the South African Supreme Court judgment goes somewhat further in considering the impact of loss of citizenship on the other rights of citizens. But the Botswana High Court judgment has been the boldest, engaging with a wide range of rights — including both the right to freedom of association and the right to vote considered by Peter Spiro — as well as moving beyond the right to family life to develop a strong argument for toleration of dual nationality based on the principle of non-discrimination. In the combination of these arguments, we can discern the grounds on which a right to dual nationality could eventually be recognized in international law.

In the meantime, considering the remarkable fact that the South African Supreme Court judgment was handed down in the same week that South African Minister of Home Affairs Aaron Motsoaledi filed an affidavit before the Constitutional Court accusing his own department’s officials of having “a cavalier and contemptuous attitude towards court orders”, it will be interesting to observe whether the Supreme Court’s view is given effect in practice.