Maarten Vink (European University Institute)

You can read an updated version of this blogpost, here.

The increased number of British nationals acquiring citizenship elsewhere in Europe in the wake of the Brexit referendum has been widely reported. New data from Eurostat, combined with statistical analysis, informs us that nearly 80,000 British citizens have acquired a European passport, six years after the 2016 referendum, who likely would not have done so had it not been for Brexit.

As soon as it became clear that a bare majority of 52% of voters in the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum (‘Brexit referendum’) had voted in favor of leaving the European Union, as Jelena Džankić already reported on GLOBALCIT in the immediate aftermath of the referendum, many British nationals realized the potential loss of rights this would afflict on them. Such a loss of rights entailed, amongst others, the right to reside, study and work in other member states of the European Union as well as in associated member states such as Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland.

For example, already in July 2016, an increasing interest in Irish passports was reported. In the years after 2016, a particularly high number of naturalizations were reported for British residents in Germany in the run up to Britain’s formal exit from the EU on 31 January 2021 (until then, British citizens were exempted from the requirement to renounce their British citizenship in order to be naturalized in Germany). Several academic studies also analyzed the Brexit naturalization effect (see for instance, Sredanović’s 2020 paper on ‘tactics and strategies of naturalization’ or Auer and Tetlow’s 2022 paper on migration and naturalization decisions, using data till 2019).

In this blogpost, I use the recently published data from Eurostat, the EU’s statistical agency, which cover statistics on citizenship acquisition up to 2021. This data now allows for a comprehensive assessment of the Brexit effect on naturalizations by British citizens in other European countries, six years after the 2016 referendum took place. As Eurostat no longer publishes data on citizenship acquisitions in the UK, from 2020, I restrict my analysis here to the impact on British citizens in Europe but it should be clear that Brexit also posed an important challenge to those non-British Europeans residing in the UK (see this report from the Migration Observatory observing that migrants from EU countries are generally less likely to naturalise in the UK, compared to non-EU migrants, but that applications by EU citizens increased after the referendum in 2016; see also various studies from the MIGZEN project).

Main trend

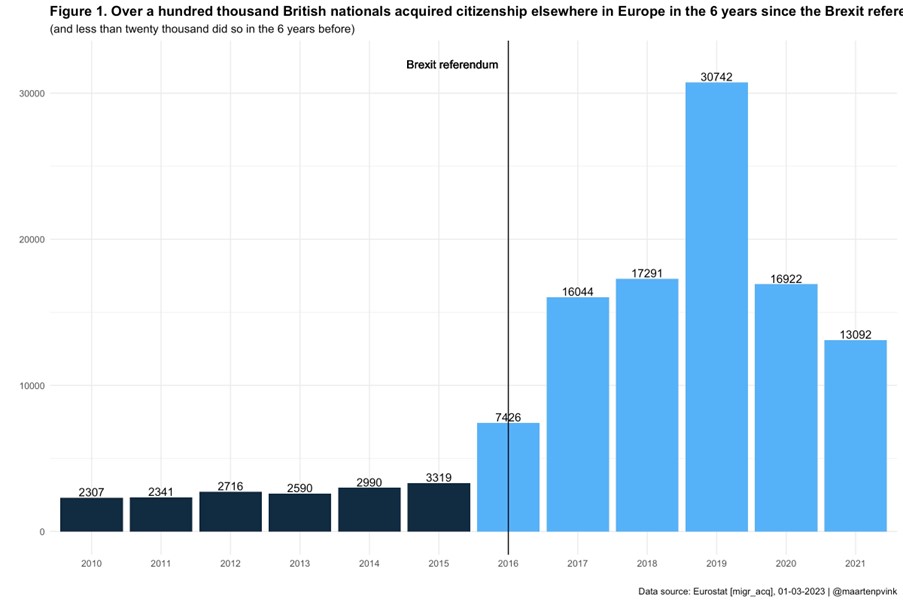

I first look at the main trend in the number of British citizens acquiring citizenship in other European countries, comparing the data reported six years before 2016 (2010-2015) with the six years from 2016 onwards (2016-2021). This trend is visualized in Figure 1. This graphic already offers an early indication of a clear Brexit effect, with the trend breaking in the number of citizenship acquisitions from 2016 onwards.

In the six years before 2016, on average, 2,710 British citizens acquired citizenship in one of the thirty other European countries studied in the report. By contrast, in the six years from 2016 onwards, the number of citizenship acquisitions by British citizens in Europe increased to 16,919 on average per year. 2019 was the clear peak year in which over 30,000 British citizens acquired another European citizenship. In total, 101,517 British citizens acquired a passport of another European country between 2016 and 2021.

Variation by country

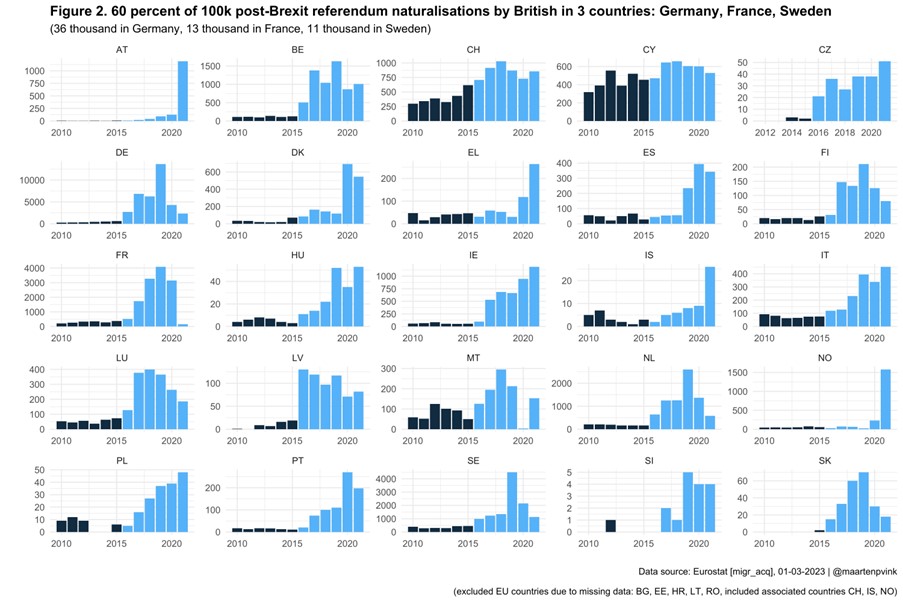

Which countries were British citizens most likely to become a new citizen of in the period after the 2016 referendum? Figure 2 visualises the main trend in 25 European countries (five countries are excluded here due to missing data in various years).

This breakdown by citizenship granting country shows that 60 percent of all post-referendum naturalisations took place in three countries: Germany, France, and Sweden. Of these, Germany by far is the country granting citizenship to most British citizens with up to 36,000 naturalisations granted from 2016. In France (13,000) and Sweden (11,000), completing the list of top 3, the numbers were considerably lower.

Why were post-referendum naturalizations so high in these three countries? Besides population size and the economic attractiveness of these countries (see here, here and here for some studies analyzing variations in naturalization rates in Europe), dual citizenship acceptance is likely an important factor. In France and Sweden, naturalizing immigrants are not required to renounce their previous citizenship, while in Germany naturalizing EU citizens are exempted from the general renunciation requirement (see here a paper analyzing the effect of changing dual citizenship acceptance in Sweden and the Netherlands). By contrast, take-up of naturalization in, for example, Norway was clearly delayed until it had accepted dual citizenship in 2020; whereas in Austria, only in 2021, take-up of naturalization by British nationals rose because of new provisions for descendants of Nazi victims which did not restrict dual citizenship (and do not require residency in Austria).

Estimating the size of the Brexit naturalization effect

While descriptive trends analysis clearly suggests a Brexit naturalisation effect for British citizens in Europe, in order to identify the causal effect of the Brexit referendum, as well as the substantive effect, we need to compare naturalisations by British citizens with naturalisations by other Europeans. After all, making a statement about causality implies a comparison with a hypothetical control group that is comparable in many ways, but not affected by the ‘treatment’ of the Brexit referendum (again, I refer here to the paper by Auer and Tetlow 2022 who apply a similar strategy).

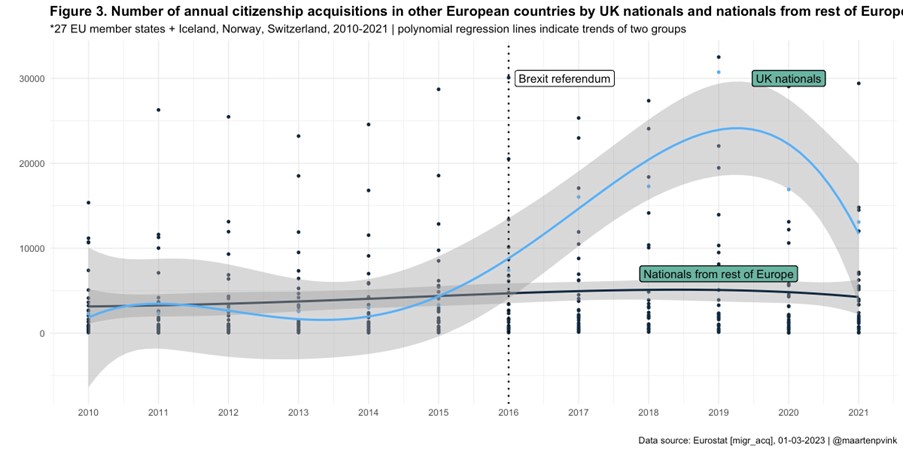

This comparison between the naturalization trends of the British and the control group of other Europeans is visualized in Figure 3. This plot evidences that a) before 2016, the average trends in naturalizations between the two groups were very similar, and b) that from 2015, the trend among other Europeans (the mean trend in naturalizations by citizens of 30 European countries) has continued around the same level, whereas naturalizations among British citizens clearly diverged (note that the plot includes confidence intervals around the so-called polynomial regression lines, which are larger for the trend in British naturalizations as these rely on only one data point for each year).

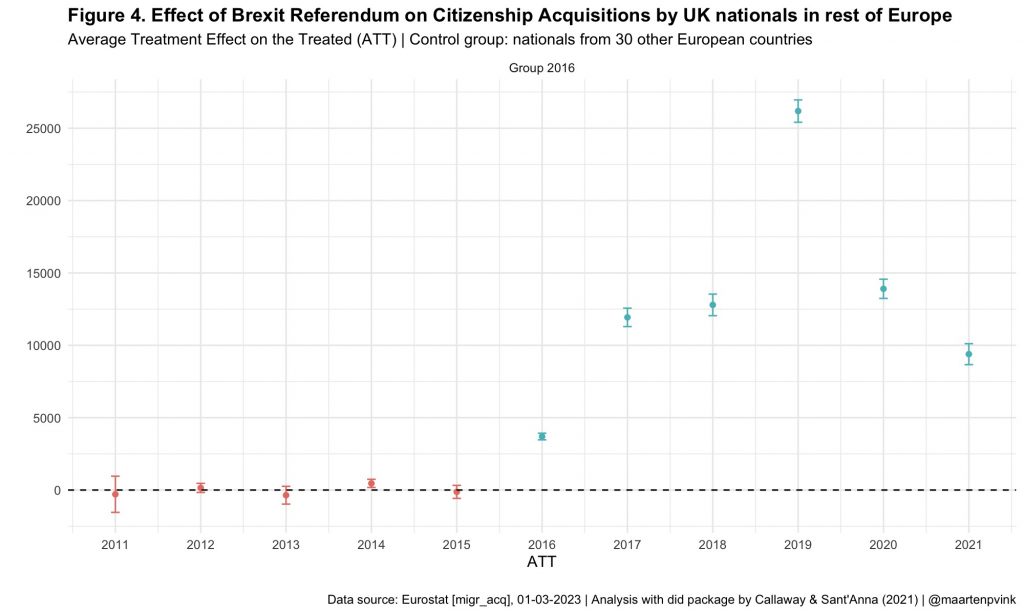

In a final step of the analysis, we can now systematize this comparison in a so-called difference-in-differences (‘DiD’) analysis, which statistically estimates the difference in naturalizations among the treatment group (British citizens) contrasting trends before and from 2016, compared with the same before/after difference among citizens from the control group (other Europeans). I make use here of the contemporary DiD approach (and the corresponding R package) developed by Callaway and Sant’Anna.

Figure 4 visualises the results of the DiD analysis. First, the plot visually confirms that we do not have evidence to reject the so-called parallel trend assumption, which is crucial in DiD analyses: there are no statistical differences in the pre-trend, i.e., the trend before treatment starts. Second, from 2016, the trends diverge with a clear peak in 2019. Third, the estimated average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) is 12.985 (with a 95% confidence interval of 12.630 – 13.338). This means that – given the trend before 2016 among British citizens and the trend from 2016 among other Europeans – in the six years since the 2016 Brexit referendum, almost 80,000 (6 * 12.985 = 77.910) British citizens acquired the citizenship of another European country and likely would not have done so, had it not been for Brexit.

Conclusion

With the exit of the UK from the EU on 31 January 2020, the number of EU citizens diminished by about 60 million British nationals resident in the UK (here, minus those who already held another EU citizenship) and an unknown number of ‘mono’ British nationals residing outside the UK. My analysis shows how around 80,000 British citizens compensated for the loss of rights due to Brexit by acquiring the citizenship of another EU or associated state. Hence, the EU lost many European citizens with Brexit, but also gained others.

I would highlight three broader implications of these findings. First, the perceived value of EU citizenship (and thus the costs of losing it) are reflected in the almost immediate action taken by British citizens in the wake of the June 2016 referendum, three-and-a-half years before the UK would eventually leave the EU, to acquire the citizenship of another EU or associated state and thus availing the mobility rights that come with EU citizenship. Second, the post-Brexit referendum naturalization dynamics highlight how Yossi Harpaz’ argument about compensatory citizenship, plays out even with the overall privileged position of the UK within the ‘global citizenship hierarchy’. While maintaining a globally highly valuable UK citizenship, the loss of mobility rights within Europe clearly motivated compensatory action by those with access to another European citizenship. Third, while there was an unmistakable Brexit naturalization effect, the available numbers also show that only a fraction of those deprived from their EU citizenship managed to compensate for this potential loss of rights. Since we know from the literature on naturalization dynamics that better educated persons are generally more likely to naturalize, especially under increasingly stricter naturalization requirements (as explained here), it is worth bearing in mind that Brexit naturalization effect is likely to reproduce and reinforce existing inequalities.

Methodological note

Eurostat provides aggregate data on the number of persons acquiring citizenship of all reporting countries in the calendar year in which the acquisition of citizenship occurred (‘migr_acq’). Available data is broken down by age, sex, and former citizenship and refers to the ‘usually resident population’ (see here for more detailed metadata). For this analysis, I use data on the total population and do not restrict by age or sex. I only use data on acquisition of citizenship by nationals of one of the 28 EU member states (in this period, including the UK) and in three associated countries, namely, Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland.

The Eurostat data can be accessed through Eurostat’s online database or, for those using R, they can be directly imported into R (see here a very useful explanation by David Reichel, whose code I built on to prepare the analyses for this blogpost). For those who want to reproduce the plots and analysis I include in this post, they can find the replication code here. For further analysis and robustness checks, I refer to the earlier cited paper by Auer and Tetlow.