By Lorenzo Piccoli (European University Institute and University of Neuchâtel), GLOBALCIT Research Associate – infographics by Giorgio Giamberini (European University Institute)

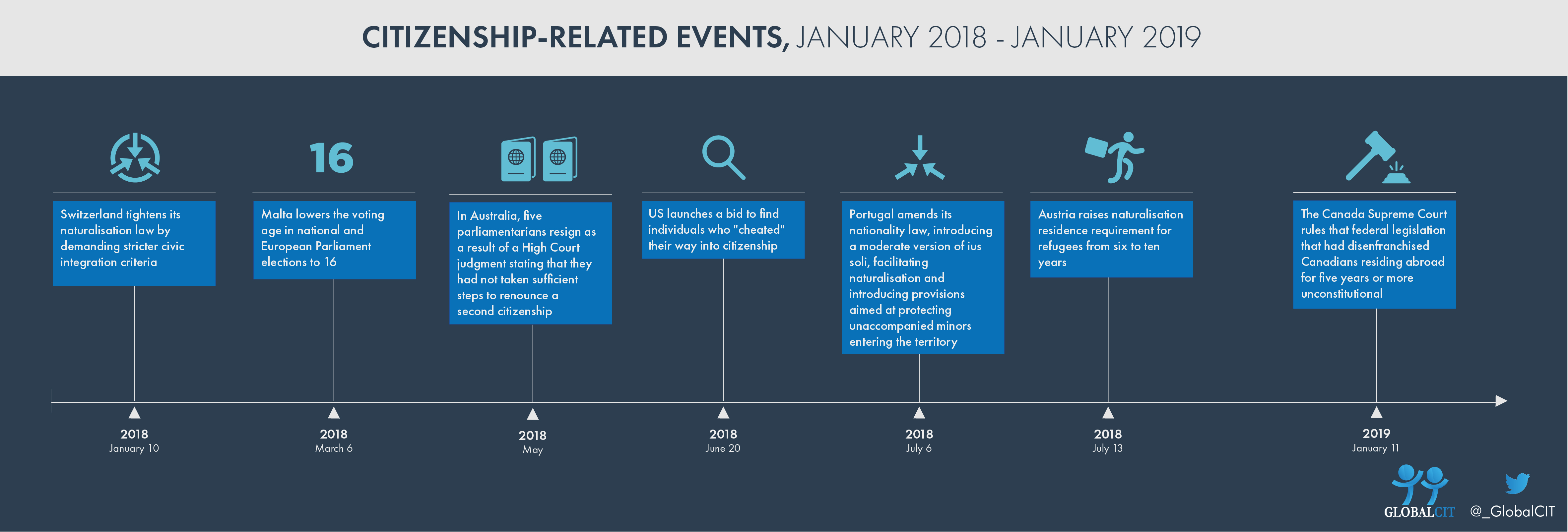

Throughout 2018, citizenship has been one of the most ubiquitous topics of political debate in a number of countries. In January the Austrian and the Italian governments entered into a spat over the possibility to offer Austrian citizenship to German and Ladin speaking people living in the region of South Tyrol. In May the United Kingdom government was embroiled in a scandal over the rights of Commonwealth citizens who arrived in the UK in the period after the Second World War. And in October, the US President Donald Trump said he will try to end the right to U.S. citizenship for babies born in the United States to non-citizens. While being a burning topic in the political discourse, the way countries regulate their membership has remained largely intact. In fact, there have been only a few changes to citizenship legislation between January 2018 and January 2019. We have mapped these reforms in a simple infographic.

In January 2018, the Swiss government’s decision to tighten naturalisation law entered into force. With its new law, Switzerland followed a European trend in introducing more stringent “civic integration” requirements, while liberalising access to citizenship in terms of residence duration requirements and dual citizenship toleration.

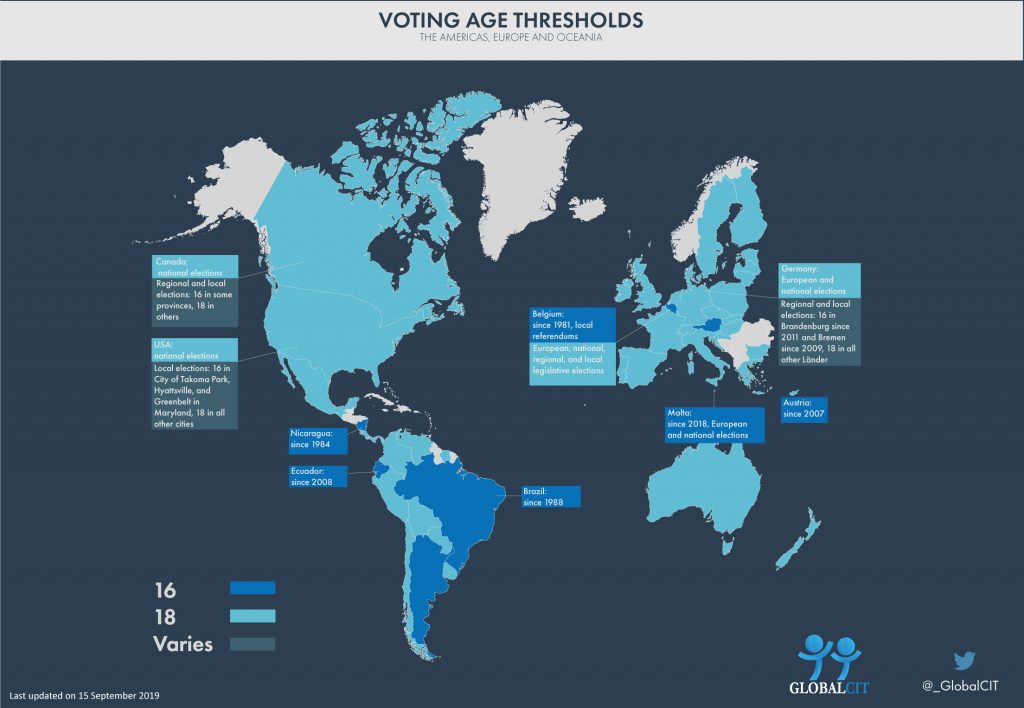

In March, the Members of the Parliament of Malta voted to change the country’s constitution and reduce the age threshold for voting in national and European Parliament elections to 16 years of age. With this reform, Malta became the second country in the European Union to lower the national voting age to 16 after Austria, where voting age was changed in 2007.

In May, following the ruling by the Australian High Court on the ineligibility of dual citizens, five members of the Parliament resigned. This has been a long-standing topic of debate that we have extensively covered on our website through a variety of articles between 2017 (Dual citizenship and eligibility to serve as a member of Parliament – the evolving story in Australia; A second Australian senator resigns because of dual citizenship; Australian senator resigns due to dual citizenship; Form over substance? Foreign citizenship and the Australian Parliament; Dual Citizen MPs in Australia’s National Parliament – the Barriers Bite) and 2018 (Australian High Court rules that dual citizens are ineligible to sit in Parliament; Dual citizenship: a shadow over Australian politics). Our partner project nccr – on the move has also covered the topic through a blog series on dual citizenship for elected politicians.

In June, the US government set up a new office of the U.S. government agency that oversees immigrants’ applications for naturalisation, aimed at identifying Americans who are suspected of cheating to get their citizenship. The US bid to find citizenship cheaters is part of a broader trend, whereby governments strip citizenship from those they deem “terrorists” or otherwise undesirable, including the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Australia. The government of Germany is currently considering the introduction of similar measures.

The amendment to the Portuguese Nationality Law has been approved by the Parliament in July. The amendment involves at least four major, along with several minor, amendments. First, the most important change undoubtedly concerns the ex lege acquisition at birth in the form of a moderate version of ius soli. Second, naturalisation has been facilitated by a lowering of the residence requirement to five years and by additional changes. Third, provisions were introduced aimed at protecting unaccompanied minors entering the territory were also introduced. Finally, new provisions aimed at protecting the principle of legal certainty were introduced following some cases that entailed annulation of several nationality acquisitions. Besides reflecting important human rights’ principles, such as the right to private life and to family unity, of statelessness prevention and of protection of legitimate expectations, above all the new law reflects a strong commitment to fully welcome all those who choose Portugal as their place of residence.

In July, the Austrian Parliament decided to raise the residence requirement for naturalisation of refugees from six to ten years. While the residence requirement for ordinary naturalisation in Austria is ten years, until then refugees had enjoyed the right to facilitated naturalisation after six years if they fulfilled the general naturalisation requirements (income, clean criminal record, German language knowledge, naturalisation test).

In December, two national parliaments modified the legislation of the respective country to allow for dual citizenship. First, breaking with its historical tradition of singular citizenship, Norway passed a law that allows citizens to retain their citizenship if they apply for another and lets naturalised Norwegian citizens retain their previous citizenship(s). The decision was part of the political platform that brought to power the current conservative government in 2017. The amendment is expected to enter into force in 2020. A few days later, the Parliament of Lesotho amended the Constitution to provide for gender equality in transmission of citizenship by marriage and to permit dual citizenship. With this reform, the country wants to facilitate contacts with people who chose to move outside of the country and take up another citizenship, with particular attention to mobility towards the large neighbouring country of South Africa.

Most recently, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled on the unconstitutionality of the federal legislation that had disenfranchised Canadians living abroad for five years or more. The case was an appeal of an earlier 2 to 1 Ontario Court of Appeal decision on a case originally brought by two Canadian citizens living and working in the United States who were denied the right to vote in the 2011 federal election. The decision will bear its first consequences already in October, when Canadian citizens will be called to elect representatives for the 338 seats of the lower house of Parliament.

These key citizenship-related events point to three features of citizenship policies around the world. First, they reveal how citizenship policy is a slow-moving target. While discussions on this topic are ever-present, actual changes in the legislation are relatively rare and take time to be implemented. Second, they highlight how legislative changes in a country are often a reflection of broader international trends such as the return of banishment through denationalisation of terrorist suspects and the progressive expansion of electoral rights towards younger cohorts and citizens who live abroad. At the same time, these events also show that inclusionary and exclusionary changes of citizenship can evolve in parallel, due to the multiplicity of actors involving in the policy-making process and their contrasting purposes. In 2019, our objective at GLOBALCIT remains to document and explain this evolution and to make it widely accessible to legal scholars, political scientists, and political practitioners.