Friedrich Poeschel (Migration Policy Centre and Eurac Research) and Inci Öykü Yener-Roderburg (Academy of International Affairs NRW and University of Cologne)

New political parties are founded all the time. Most of them never reach a significant share of the vote and eventually give up. So why did the newly founded ‘Democratic Alliance for Diversity and Awakening’ (Demokratische Allianz für Vielfalt und Aufbruch, DAVA) provoke a backlash in Germany? Various government heavyweights as well as opposition politicians reacted with disapproving statements – when normally the most effective way to keep a new party down is to ignore it. In short, we saw this uproar because the new party has ties to Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoǧan, stands to benefit from a citizenship reform that was passed only some days earlier, and appears at a time of rising polarisation within society over Gaza.

Parallels to parties in the Netherlands, Austria and France?

The key bit of information about the new party was its founders and the candidates it announced for the upcoming European elections: all have become known as staunch supporters of Turkish president Erdoǧan and his Justice and Development Party, the AKP (‘Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi’). One is the spokesperson of a lobby organisation (Die Union Internationaler Demokraten, UID) that stages events for AKP election campaigns targeted at Turkish citizens living in Europe. Another was president of an international aid organisation banned by the German Ministry of the Interior for channeling funds to Hamas. One was reportedly a member of the social democrats for 30 years, during which time he was mainly known for supporting Erdoǧan.

In its programme, DAVA emphasises non-discrimination, financial improvements and a better treatment of Islam. The more concrete propositions include Turkish as a foreign language option in schools, higher pensions, the legal recognition of Muslim communities, replacing “racist narratives” in the media with a “more positive” image of Islam, correcting false portrayals of Islam in schoolbooks, including Islamophobia in anti-discrimination legislation, a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine, raising the minimum wage, as well as the right to old-age care received at home.

Commentators have drawn parallels to political parties in other EU countries. In the Netherlands, ‘Beweging DENK‘ was founded by two members of the Dutch parliament who were expelled from the social democrat faction when they opposed stronger monitoring of several conservative Turkish organisations. In Austria, ‘Soziales Österreich der Zukunft‘ (SÖZ) was founded by a vice-president of the (predecessor of) UID, the lobby organisation mentioned above. In France, the ‘Parti égalité et justice‘ (PEJ) has a strong affiliation with the Council for Justice, Equality, and Peace (Cojep, also known as TIKA), a non-governmental organisation that serves as a support base for AKP wherever it operates, but particularly in France. Interestingly, the acronyms of most parties also have a meaning in Turkish. ‘DENK’ translates as equal or balanced, ‘SÖZ’ as promise and the meaning of ‘DAVA’ is somewhere between cause, case, law suit, and litigation which originates from the Arabic word ‘Dawah‘, widely known as the call to Allah, i.e. an invitation to join the Islamic faith that has been used in the Turkish political Islamist spectrum.

Each of these parties has raised concerns that they might represent a subsidiary of the AKP, or even “the long arm” of Erdoǧan. While representatives of these parties regularly dispute such claims, it is rather easy to find their (sometimes ardent) endorsements of Erdoǧan and AKP policies on social media, while it is not at all easy to find instances of criticism. However, could it be that diaspora members themselves set up independent parties that reflect political camps in the country where the diaspora originated? This would stand in sharp contrast to previous AKP-related activities in Germany, which have been characterised as hierarchical and top-down (e.g. Yener-Roderburg, 2020). If any of these parties were integrated into some command structure that begins in Ankara, this would amount to foreign interference in elections. Such command structures might not only be used to mobilise the diaspora for political aims but potentially also to exercise control over it (e.g. Adamson, 2019). While it is beyond the scope of this text to discuss Erdoǧan’s vision for the diaspora of Türkiye, suffice to say that he has reservations about the diaspora’s ‘integration’. He once stated that “assimilation is tantamount to a crime against humanity”.

Possibly linked to a reform of citizenship?

DAVA is not the first political initiative of conservatives in Germany’s Turkish community. In fact, such efforts go back a long way. The ‘Demokratische Partei Deutschlands‘ (Democratic Party of Germany) was founded already in 1995 but dissolved in 2002. Setbacks were also experienced by the ‘Bündnis für Innovation und Gerechtigkeit’ (The Alliance for Innovation and Justice, BIG), established more recently, and the ‘Allianz Deutscher Demokraten’ (Alliance of German Democrats, ADD), whose founder is known to have affiliations with Erdoğan. However, these earlier parties that were established by Turkish-origin people in Germany failed to make a significant impact in elections. For example, when Erdoğan explicitly urged support for ADD in Germany’s 2017 general elections, the ADD increased its vote share but still fell short of securing the desired votes and subsequently dissolved. Did these parties fail partly because a large part of the Turkish diaspora in Germany could not vote? Although eligible, many never became German citizens. A key reason is that citizenship law required Turkish and other non-EU citizens to give up their earlier citizenship.

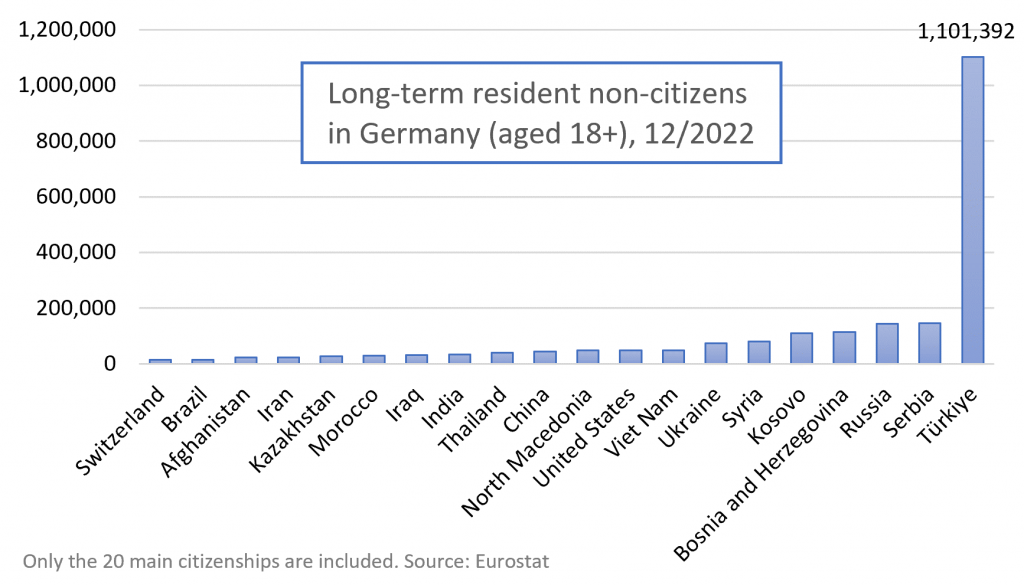

This changed with a reform of citizenship law that passed German parliament on 19 January 2024 and now allows for dual citizenship. The founding of DAVA was announced only three days earlier. While these events are not necessarily linked, more Turkish long-term residents in Germany – very many of whom already qualify for German citizenship – might now choose to take it up. They are by far the largest group to benefit from the reform (Figure 1), which DAVA founders might see as a source of many new voters over the coming years. Members of the opposition warned the government in December 2023 that the reform might encourage the foundation of an AKP-inspired party. The strong reactions by politicians to the news of DAVA’s establishment can therefore also be understood as moves in a political blame game.

In the short-term, DAVA’s stated motivation is to participate in the upcoming elections to the European Parliament. In contrast to German federal or state election, European elections do not have a minimum threshold of 5% (which entails that seats are allocated only to parties receiving at least 5% of the votes cast, with very few exceptions). This raises the chances of small parties considerably: in the last European elections, just 0.7% of the votes in Germany were enough to win a seat. During the election campaign, DAVA is poised to utilise channels akin to those used by the AKP in Turkish elections to reach the diaspora especially in Germany. Although the upcoming elections (in June) leave little time for effective mobilisation, these channels may help DAVA to secure a few seats in the European Parliament: they extend beyond UID and include the numerous DITIB mosques, a longstanding instrument of the Turkish state (e.g., Arkilic 2022; Yener-Roderburg & Yetis 2024).

Partly for the aforementioned reasons, DAVA is garnering more attention than previous parties. However, there is an additional dimension: the creation of DAVA can also be regarded as a result or a continuation of growing political frustration and polarisation in Germany.

Will DAVA become relevant in German politics?

Opinions about how many voters DAVA might attract vary widely – from essentially none up to 5 million (as the founders say). German citizens who in some way may be considered members of the Turkish diaspora appear to vote mainly for centre-left parties already in parliament (e.g. Krumm, 2018). But Turkish citizens who are residents in Germany and have participated in Turkish elections since 2014 have shown substantial backing of the AKP and Erdoğan (e.g., Yener-Roderburg and Yetis 2024). If many of those who retained the Turkish citizenship value it especially highly (Dronkers and Vink, 2012), then especially Turkish nationalists are likely to be over-represented in this group, and the voting behaviour of the German citizens will not necessarily carry over to new voters with dual citizenship. Krumm (2018) in fact sees a split along citizenship with those who have taken up German citizenship leaning towards the centre-left while those who remain Turkish citizens and have not yet taken up German citizenship tilting towards the centre-right.

Perhaps most importantly, new parties can be successful whenever they respond to some “need in society” or broad popular movement. In the Turkish community, frustration is growing and some feel that they are simply not politically represented. Several events in recent months may have contributed to a sense of distance and alienation, notably the Hamas massacre of Israelis and the following Israeli invasion of the Gaza Strip. The pro-Israel standpoint of the German government contrasted with pro-Palestine demonstrations, and appalled disbelief of the anti-Semitism displayed in such demonstrations contrasted with similar outrage over perceived indifference to the suffering in Gaza. News of a far-right fringe meeting that discussed large-scale expulsion of immigrants from Germany (including citizens) did not exactly help, even though civil society responded with huge demonstrations over weeks.

Whether DAVA can tap into these political feelings depends also on its logistical capacity and wider appeal. DAVA’s ongoing mobilisation efforts, facilitated through its associations with UID and DITIB, have the potential to expand its voter base and attract media attention. While DAVA intends to appeal to various ethnic or religious minorities, its candidates and activities do not show this diversity. If DAVA becomes an ‘ethnic party’ with some success, this might provoke a response of other voters that ironically increases support for right-wing populists (Koev, 2015).

Given its logistical apparatus and experience, DAVA can probably run successful campaigns, potentially leading to representation in the next European Parliament. A similar success in German general elections is mostly not realistic due to the 5% threshold. However, while DENK won only 2.1% in its first show at Dutch general elections (2017), it won around 8% in large cities and up to 20% in some districts. It is therefore not difficult to imagine DAVA winning seats at local level and even in certain states. Still, the notion that it could influence Germany’s political landscape to mirror the AKP’s authoritarian regime with a few representatives if any is unrealistic. Instead, the ‘success’ of DAVA could be to convert a few seats into a very visible presence in the political debate, for example using controversial motions and high-profile media appearances, something that DENK has arguably achieved in the Netherlands.

References

Adamson, Fiona B. “Non‐state authoritarianism and diaspora politics.” Global Networks 20.1 (2020): 150-169.

Arkilic, Ayca. “‘Islam does not belong to Germany’: Germany’s response to Turkey’s changing relations with its diaspora.” In Diaspora Diplomacy, pp. 168-92. Manchester University Press, 2022.

Dronkers, Jaap, and Vink, Maarten, “Explaining access to citizenship in Europe: How citizenship policies affect naturalization rates.” European Union Politics 13.3 (2012): 390-412.

Koev, Dan. “Interactive party effects on electoral performance: How ethnic minority parties aid the populist right in Central and Eastern Europe.” Party Politics 21.4 (2015): 649-659.

Krumm, Thomas. “Germany’s Turkish voters –what do we know?”. Turkish-German University Istanbul mimeo (2018).

Yener-Roderburg, Inci Öykü. “Top-down satellites and bottom-up alliances: The case of AKP and HDP in Germany.” Political Parties Abroad. Routledge (2020).

Yener-Roderburg, Inci Öykü, and Erman Örsan Yetiş. “Building party support abroad: Turkish diaspora organisations in Germany and the UK.” Politics and Governance 12 (2024).