Abdulrashid Solijoniv, Peter Wolf and Adhy Aman (International IDEA)

Out-of-country voting (OCV) is not a novel practice. However, it has not necessarily kept up with the fast-paced cross-border mobility of people. Today, voters abroad may face many challenges: they may not be able to vote because of stringent voter registration rules; even if registered, voters may find difficulty casting their votes due to limited voting methods available; or voters may have to travel long distances due to a limited number of polling stations available in foreign countries. Such challenges affect the degree of participation of citizens living or staying temporarily abroad in elections held in their homeland.

In 2021-2022, the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) conducted two separate surveys to better understand OCV practices and how they affect voter turnout abroad. The first survey covered the following topics:

- Restrictions imposed on OCV

- Methods and mechanisms of OCV registration

- Voting methods from abroad

- Technologies used for OCV

- Obstacles that affect voter participation abroad.

The second survey collected only statistical data, such as OCV turnout, total number of votes cast from abroad, and voter registration rates for OCV. In the first survey, data have been collected from 62 countries, while in the second survey, data have been collected from 98 countries. There were 49 overlapping countries in both of these surveys, which allows pooling data from both surveys and conducting joint analyses.

The results

The findings reveal that OCV is limited to certain groups only in 10% of the countries researched. In these countries, OCV is restricted to civil servants (6 countries), students (5 countries), and military personnel (2 countries). This indicates that the majority of countries surveyed acknowledge the right of enfranchisement for all citizens living abroad.

Results also indicate that the length of stay abroad or in the country of origin is a rare restriction nowadays for casting votes from abroad – only 8% countries covered in the survey impose such restrictions. In most of the countries surveyed, the right to vote can be exercised as long as the person remains a citizen of the country.

Results show that in 87% of countries, OCV registration method is active, which means that voters abroad have to take action in order to get registered. Only in 11% of countries OCV registration is passive and voters do not have to take action in order to register to vote from abroad. The voter lists in countries with passive method are normally created either using the information available in the embassies or the voter lists provided by the electoral management body (EMB) to the embassies abroad.

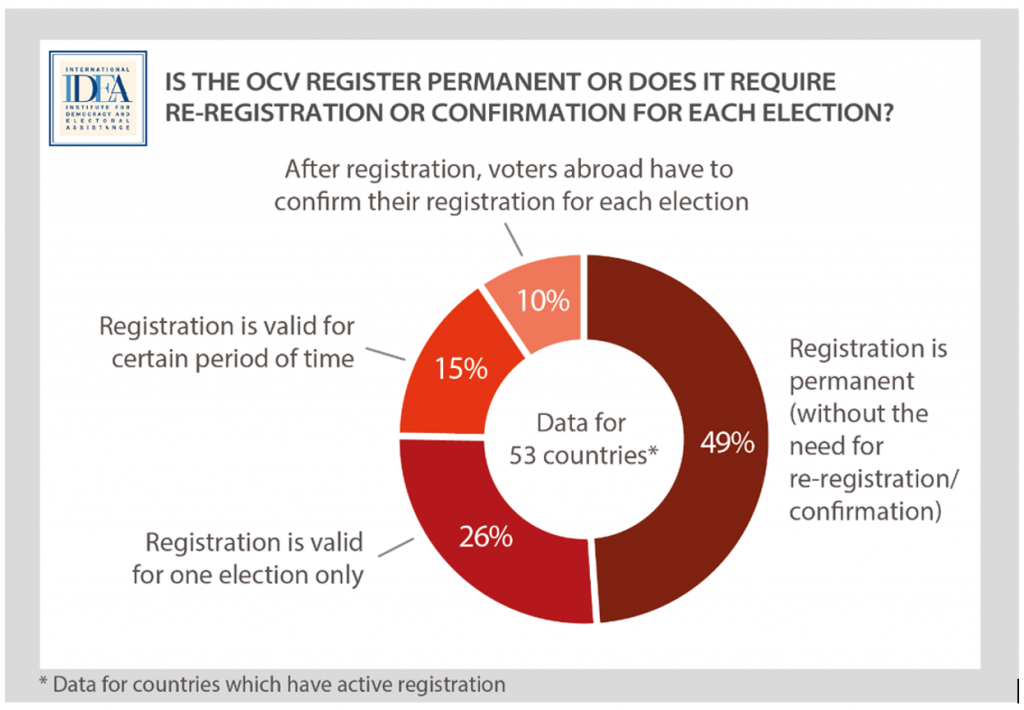

Among those countries which require active registration abroad, in almost half of the countries (49%) OCV registration is permanent (Figure 1). In a quarter of countries (26%), OCV registration is valid for one election only. In 15% of countries, OCV registration is valid for certain period of time, and in 10% of countries, registered voters have to confirm their registration for each election.

Figure 1: If ACTIVE registration, is the register permanent or does it require re-registration or confirmation by the voter for each election?

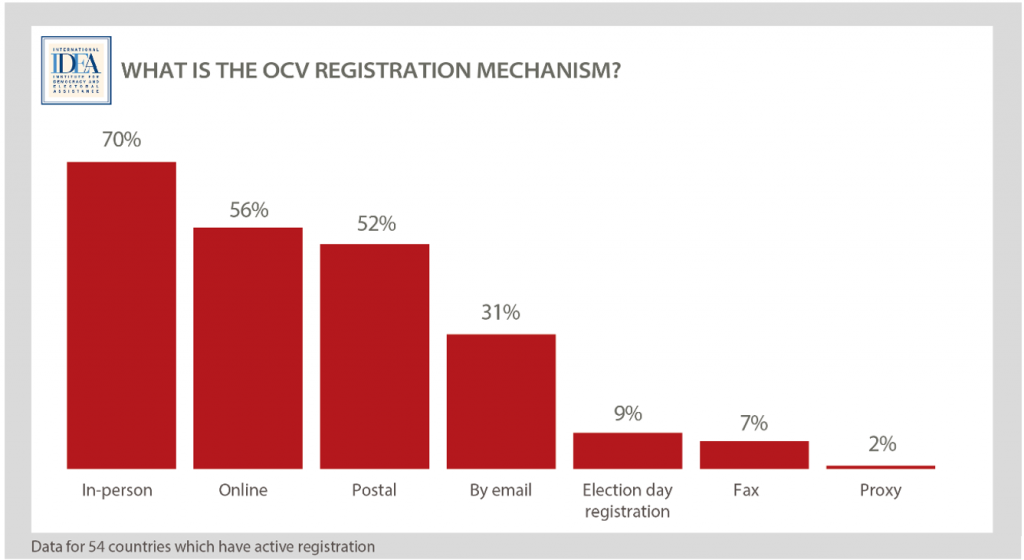

Amongst countries with active registration abroad, in 70% registration can be made in-person, in 56% online registration is possible, in 52% voters can send registration documents by post, and in 31% registration can be made by email (Figure 2). Election day registration, registration by fax and by proxy are much less used methods of voter registration abroad. As with anything in life today, online facilities are growing also for OCV purposes. Given that some voters live far from the nearest diplomatic mission, allowing registration remotely is helpful.

Figure 2: If ACTIVE registration, what is the OCV registration mechanism?

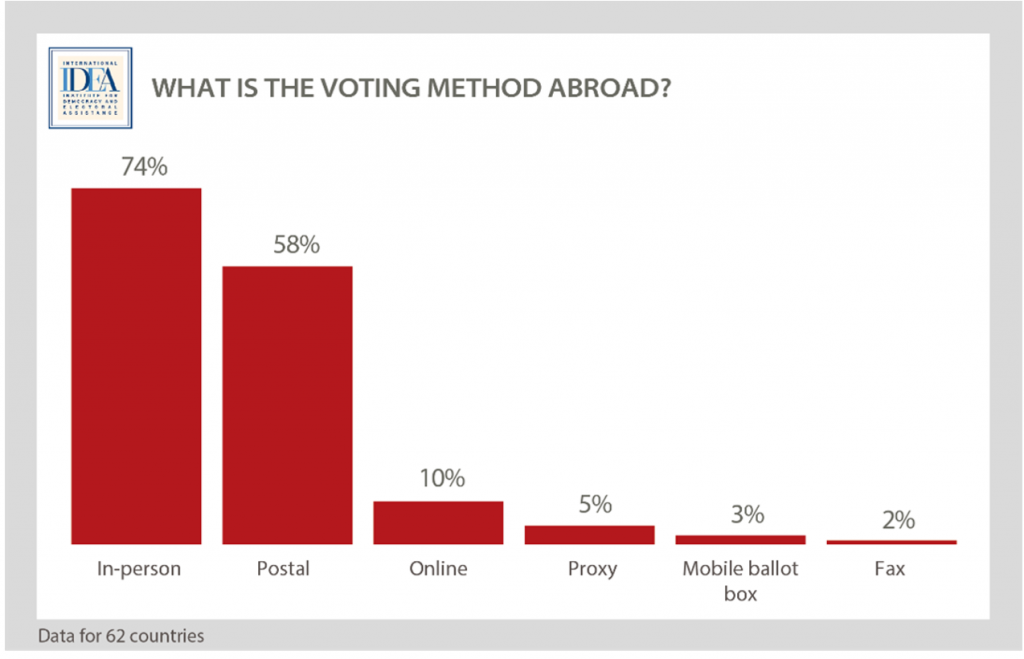

Looking at how voters cast their votes, one can observe that voters can vote in-person from abroad in nearly three forth of countries (74%), while postal voting from abroad is available in 58% of countries (Figure 3). Online voting is available only in 10% of countries. Proxy voting, mobile ballot boxes and voting by fax are rarely used practices in OCV. A large majority of countries surveyed still rely on the dependable and robust in-person voting. However, this may not be convenient for voters living far from the polling station and thus may have a negative impact on turnout. Postal voting may help remote voters, but it is not without problems and relies on effective postal service, which may not be available in every country.

Figure 3: What is the voting method abroad?

The survey asked respondents about the use of technology for voter identification and casting the vote from abroad. The results show that only 25% of countries covered by the survey use voter identification technologies for OCV. The survey also found that electronic technology for casting the vote from abroad is used only in 10% of countries. The uptake of using technology for OCV is clearly still on the low side.

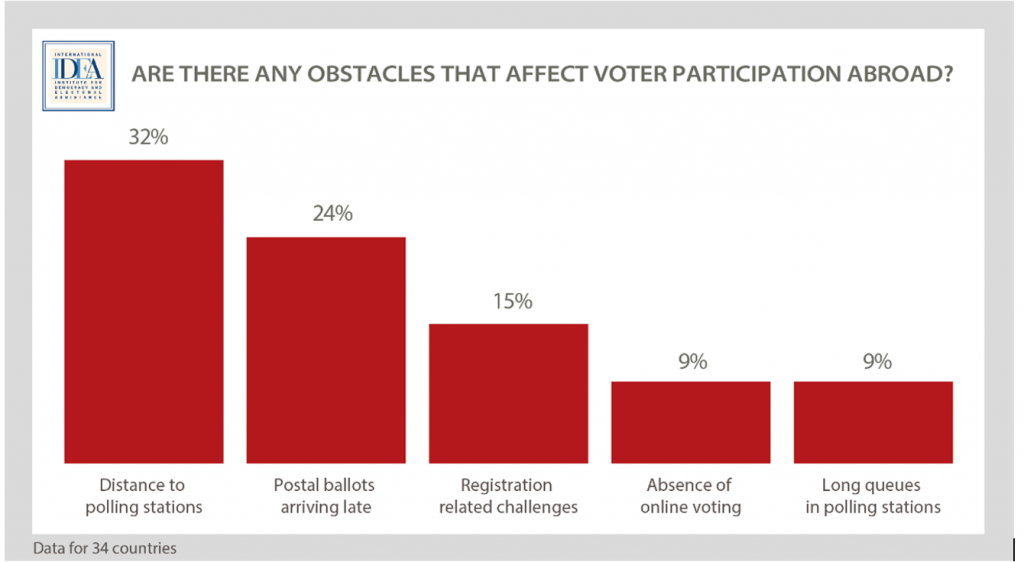

Very often, voters abroad complain about the challenges related to OCV. The survey found that the most common obstacles for out-of-country voting, as indicated by respondents (Figure 4), were distance to polling stations (32%), late arrival of postal ballots (24%) and challenges related to registration (15%). Only 9% of respondents complained about the absence of online voting and long queues in polling stations abroad. Distance being the top obstacle shows that voters abroad tend to live far from any in-person voting stations. The fact that 24% expressed a postal ballot problem shows a good proportion of voters rely on postal voting. Therefore, countries need to think of ways to improve OCV, potentially through technological means and finding alternatives to postal voting.

Figure 4: Are there any obstacles that affect voter participation abroad?

OCV turnout

Even though there is vast academic research on voter turnout, a quick literature search reveals that OCV turnout is a very much unresearched area. The reason for this lack of attention to the topic could be that data on OCV turnout have not been available so far. We hope that our new dataset on OCV turnout will trigger academic interest and a better understanding of what helps or prevents voters from casting their vote from abroad. What is presented below is only the overall descriptive analyses of the data.

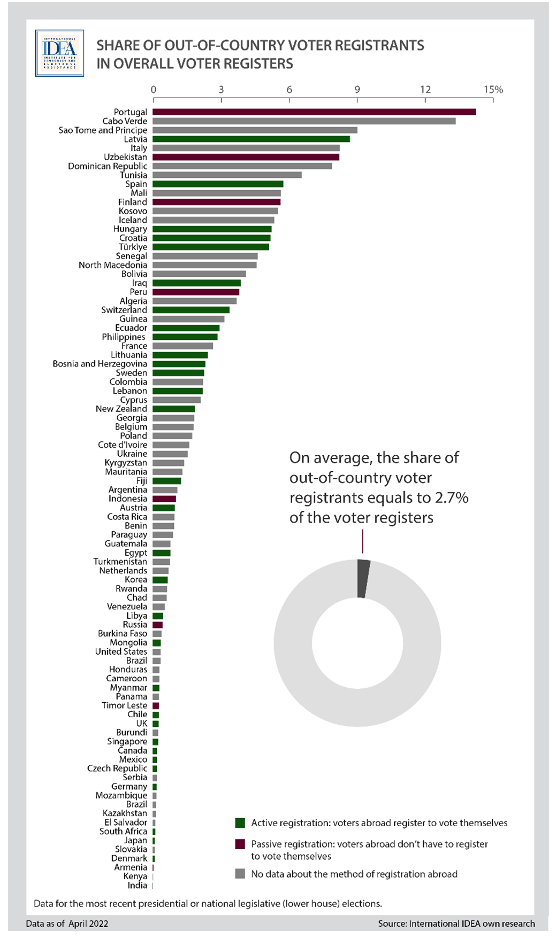

Figure 5 below presents the share of OCV registrants in overall voter registers. In general, among the 87 countries included in the analysis, the mean share of OCV registration amounts to tiny 2.7%. However, in 8 countries, the share of OCV registrants exceeds 6%, and these countries differ on many dimensions, such as the level of democracy, the level of economic development, and even location. Portugal and Cape Verde can be treated as outliers – both having shares of OCV registrants of more than 13% . Obviously, further research would be needed to identify the causes of the extent of OCV registration in relation to overall voter registry. Figure 5 also reveals that the method of voter registration doesn’t have much effect on the degree of OCV registration – countries with both active and passive registration methods are evenly spread out across the bar chart.

Figure 5: Share of OCV registration in overall registration

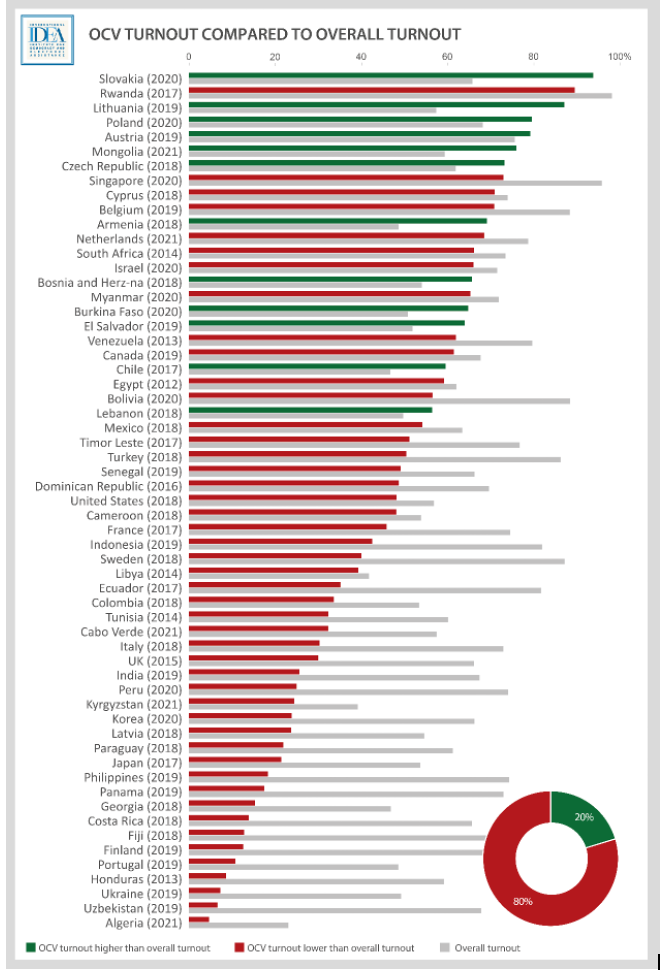

Figure 6 below presents the level of OCV turnout as compared to the overall turnout. Only in 20% of countries covered by the survey, OCV turnout exceeds the overall turnout. Overall, this indicates that voter participation from abroad is very much lower than that in the country. In more than half of the countries, the difference is very significant. This finding offers the proponents of enfranchisement of the citizens living abroad some food for thought. However, in some settings, where the votes of out-of-country voters are significant for domestic political decision making, such low levels of OCV participation may trigger a need for better understanding of the causes that prevent voters abroad from casting their vote.

Figure 6: OCV turnout compared to overall turnout

What has been presented in this blogpost is a snapshot of the data collected by International IDEA. More in-depth analyses have been published by the institute on its website. We invite researchers to use the data for further analyses, and in case users will be interested to contribute the missing data, we would be glad to add those data to the dataset. The current data from the surveys are available upon request. Please write to elections@idea.int for requesting the data or for any other enquiries.