Luuk van der Baaren (European University Institute and University of Copenhagen)

This is the second post in a series of blog posts on The Global State of Citizenship, accompanying the launch of an updated version of the GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset. A first blog post on discrimination in citizenship law was published on May 1. The v2 version of the Dataset will include data on all modes of acquisition and loss of citizenship in 191 countries, covering the years 2020-2022; as well a longitudinal data on dual citizenship acceptance worldwide, 1960-2022. The updated Dataset will be launched on Tuesday 16 May at https://globalcit.eu.

Recent years have seen a resurgence of states employing citizenship deprivation as a security measure. This trend has been well-documented, among others in a report published in 2022 by the Global Citizenship Observatory (GLOBALCIT) together with the Institute of Statelessness and Inclusion (ISI). The forthcoming update of the GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset, which will be launched on 16 May and include data up to 2022, allows us to analyse these deprivation provisions in national law in comparative detail – and the intention is gradually to add coding for the earlier versions of the laws, enabling the trends to be tracked over time, as is already the case for dual citizenship.

The Big Picture

The GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset contains four categories providing for loss of citizenship related to security grounds. These are classified under four different ‘modes’ of loss of citizenship:

- Service in a foreign army (mode L03)

- Other service to a foreign country (mode L04)

- Disloyalty or treason (mode L07)

- Other offences (mode L08)

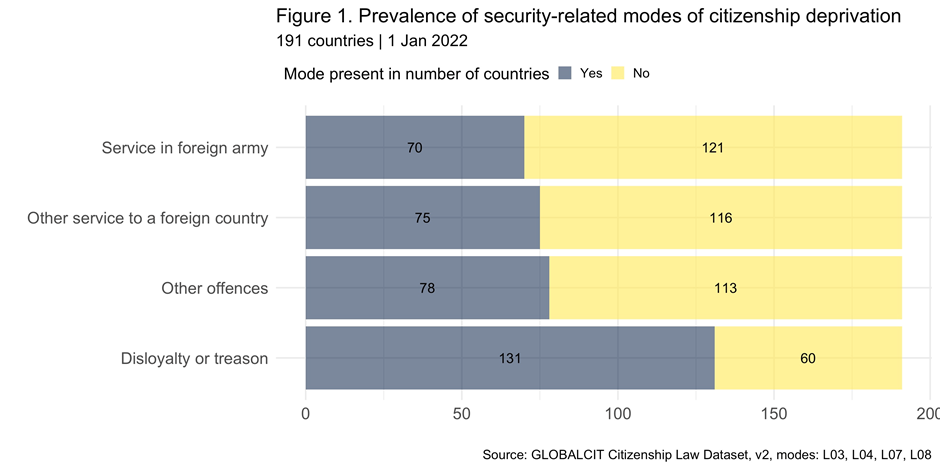

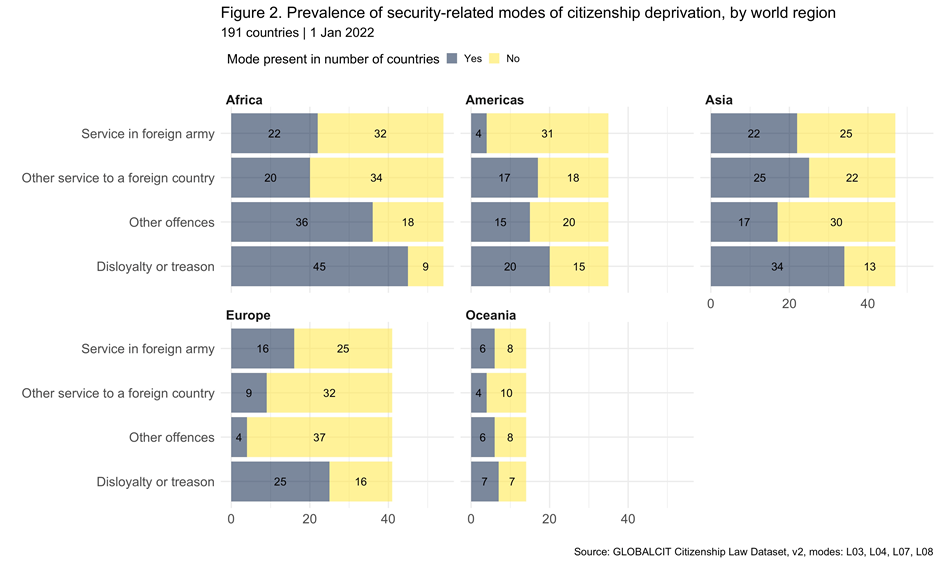

The dataset shows that security-related loss provisions are relatively common. Nearly 80% of the countries have incorporated at least one of these grounds for loss in their citizenship legislation. There is significant regional variation, as a relatively large number of countries in Africa and Asia provide for three or all four of the abovementioned grounds, while in Europe and the Americas, a relatively large share of the countries have only enacted one of these grounds or none at all.

Zooming in, it becomes apparent that disloyalty is by far the most common security-related deprivation ground (see Figure 1). Overall 131 countries provide for loss of citizenship on this ground. Such provisions are common across all world regions, with a prevalence ranging from 50% in Oceania to 80% in Africa (see Figure 2). Notably, deprivation of citizenship based on a broad ground of disloyalty (L07) is also the only security-related deprivation ground that exists in more than half of all the European countries. For the other grounds of citizenship deprivation, there is more regional variation. Provisions for loss due to military service or other services to a foreign service are relatively common in Africa and Asia but are not as common in other regions. While two-thirds of the African countries provide for loss of citizenship due to other offences (not relating to disloyalty), less than 10% of the European countries provide for loss on that ground.

The dataset also shows that in the abundant majority of cases, citizenship is lost on security-related grounds by deprivation, which means that loss can only take place if the authorities take action in order to deprive persons of their citizenship. In a minority of cases, loss of citizenship takes place by lapse, which generally means that citizenship is automatically lost when a person commits an act that is covered by the provision. Nonetheless, lapse of citizenship can only be enforced once the authorities discover that such an act has taken place. This can be a prolonged process and trigger significant uncertainty.

Service in a foreign army or other service

Citizenship can be lost in 70 countries for serving in a foreign army. Such a provision of loss is generally applicable in 53 countries, while in 17 countries, it only applies to certain groups of citizens, typically those who acquired citizenship by naturalization. Some countries restrict the provision to military service provided to a hostile state. Generally, the deprivation of citizenship only applies if a warning has been issued to the affected person, and if they fail to abandon military service within a specified period.

Similarly, in 70 countries, citizenship can be lost for providing services (excluding military service) to a foreign state. The loss provision is generally applicable in 45 countries, while in 30 countries, it only applies to certain groups of citizens, typically those who acquired citizenship by naturalization. In certain countries, a person can lose citizenship for taking up any official- or governmental position in a foreign country. However, these provisions are usually restricted which entails that they only apply to positions considered a threat to state security or in cases where a warning has been issued that requires the affected person to resign from the position.

Disloyalty or other offences

Disloyalty refers to any behaviour or offence that is based on a concept of disloyalty or harm to the interests or security of the state, including offences such as treason. In 43 countries, the provision is generally applicable to all groups of citizens, while in 88 countries it is restricted to certain groups of citizens (usually citizens by naturalisation). In a large share of countries, citizenship can only be lost on this ground if there is a prior conviction. The person must usually have been convicted for a crime against the security of the state or a crime against the interests of the state. In other states, the relevant provisions do not have the abovementioned safeguard and are broader in scope. In these cases, harming state security or state interests can be sufficient reason for loss of citizenship without any prior conviction. These provisions tend to be particularly broad in scope if only aturalized citizens are affected.

In 78 countries, citizenship can be lost due to criminal offences. In four countries, the loss provision is generally applicable, while in 74 countries it is restricted to certain groups of citizens (usually citizens by naturalisation). In a majority of countries the provision is only applicable if a person has been sentenced to imprisonment for a minimal period of time – ranging from twelve months to ten years. In certain countries, loss of citizenship can occur if a person has been convicted for an act that is punishable with imprisonment for a specified period of time, which is a lower threshold. If the provision is only applicable to naturalized citizens, it can often only occur if the act was committed within a certain period of time after citizenship was acquired (e.g. five or ten years).

What to make of the instrumentalization of citizenship deprivation for security reasons?

While their scope and form vary, provisions for security-related deprivation of citizenship are widespread. A longitudinal study conducted by GLOBALCIT and ISI shows that between 2000 and 2020 there is a clear trend of increased prevalence and greater applicability of nationality deprivation on grounds related to disloyalty. In addition to that, pre-existing deprivation provisions can be weaponized for stripping persons of citizenship due to new-found security concerns. These developments have been referred to as “the return of banishment”.

Security-related deprivation of citizenship creates a risk of arbitrary deprivation of citizenship, which is generally considered to be contrary to international customary law. The dataset shows that security-related deprivation grounds often allow for citizenship stripping without due process. The provisions are often ambiguous (e.g. referring broadly to “national security”) which gives rise to legal uncertainty. The dataset also shows that the provisions often solely apply to certain groups of citizens (generally persons who were not born as citizens) which amount to discriminatory treatment.

Contrary to international standards as outlined in the Principles on Deprivation of Nationality as a National Security Measure, many of the loss provisions do not provide for adequate safeguards against statelessness. This can result in an extremely precarious situation for both the affected persons as well as their dependents. Even if safeguards against statelessness exist, the dataset also shows that in a significant number of countries it is either legally or practically impossible to renounce citizenship. For these involuntary dual citizens, this status might turn into a liability as it makes them prone to being deprived of their citizenship.

All in all, instrumentalizing citizenship policies for presumed security purposes can lead to highly questionable outcomes that frequently contradict the international legal obligations of states as well as international standards. By closely monitoring developments of these provisions, the GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset provides a tool for researchers interested in analysing global trends and regional variation, as well as an empirical starting point for public advocacy addressing the pervasive concerns about states’ adherence to international standards.