Maarten Vink (European University Institute)

This is the third in a series of blog posts on The Global State of Citizenship, accompanying the launch of an updated version of the GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset. The first blog post on discrimination in citizenship law was published on May 1. The second blog post on security-based citizenship deprivation was published on May 12. This blog post highlights what is new in the updated version of the Dataset compared to its predecessor.

Today, GLOBALCIT launches an updated version of the GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset, with coverage extended to 191 countries. The Citizenship Law Dataset includes updated information on all modes of acquisition and loss of citizenship, covering the years 2020 – 2022; and introduces longitudinal data on dual citizenship acceptance worldwide, 1960 – 2022. It provides systematic information on the ways in which citizenship can be acquired and lost around the world. The Dataset is organised around a comprehensive typology of modes of acquisition and loss of citizenship, capturing 28 ways in which citizenship can be acquired, and 15 ways in which it can be lost. This information facilitates comparisons of the rules applicable to similar groups across countries, and provides a global outlook on the current state of citizenship law (for a longer introduction to the comparative methodology, see here).

Expanded, updated and corrected information

The updated version of the Dataset covers legislations in force on 1 January of the years 2020 to 2022 in 191 states (with an additional 5 micro-states and 5 predecessor states covered in the new longitudinal dual citizenship policy data, discussed below). Compared to the 2021 version of the Dataset, we added coverage of Thailand (a new country report with detailed information on the history and current state of citizenship law in Thailand will be published soon; detailed information about countries covered in the Dataset is available through our country profiles). Finally, version 2 includes corrections of coding for 2020, drawing on feedback from experts, new information, or revised insights into the most appropriate interpretation of specific legal provisions. All updates and corrections are listed in a new section 4 of the updated Codebook (available in the EUI’s institutional repository).

As has been the case previously, the data can be explored through two online databases on modes of acquisition of citizenship and modes of loss of citizenship. These databases allow two types of search: a) list all modes of acquisition or loss of citizenship in one country (select the country you are interested in); or b) compare a mode of acquisition or loss of citizenship across countries (select the mode of you are interested in and compare across all or selected countries).

The databases provide information on the relevant article in the law for a provision, the procedure of acquisition or loss, as well as a summary description of the provision (‘Conditions’), and a standardized categorization of the type of provision that allows comparing similar types of provisions across countries (‘Category’). The information searchable in these online databases is archived in two data files, row-ordered by country, year and mode. The complete or selected information can be directly downloaded from the online databases (in .csv or .xlsx files), but users are advised to refer to the files archived in the data repository when citing the data.

In addition to the qualitative information searchable in the online databases, the Dataset includes a data file coding the presence and type of provision regulating the acquisition or loss of citizenship in a country in a particular year, row-ordered by country and year, and binary and categorical citizenship law variables in columns.

The ‘big picture’

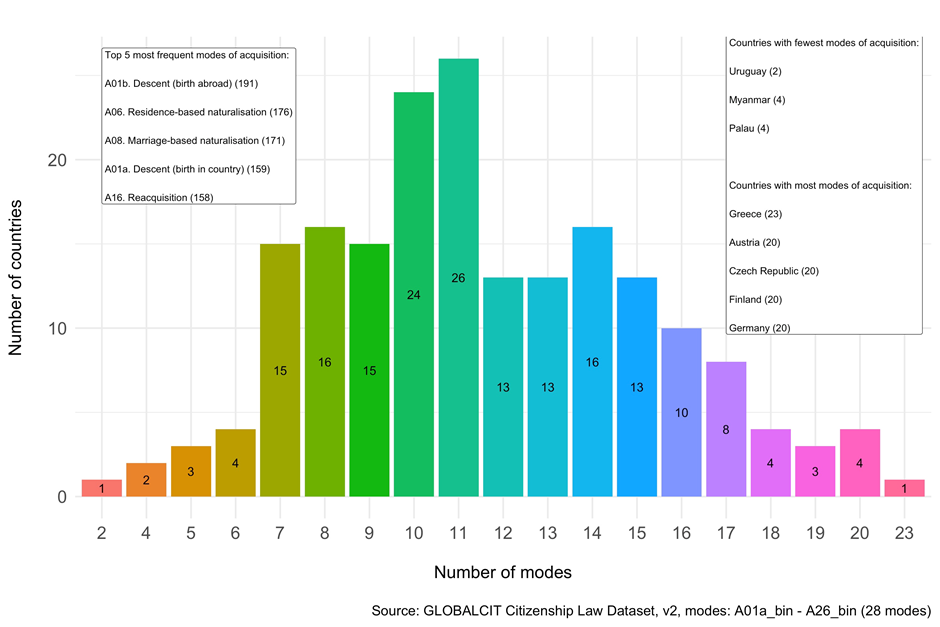

For a ‘big picture’ description of the global state of citizenship, I start by assessing the frequency of the number of applicable modes of acquisition of citizenship across countries. I look at whether or not each mode of citizenship acquisition is present in a country and then sum up the number of modes in each country.

Figure 1. How many modes of acquisition of citizenship in each of 191 countries, in 2022?

The results are visualised in Figure 1, which shows that, in 2022 the median number of modes of acquisition of citizenship across the 191 countries included in the Dataset is 11, out of a total of 28 acquisition modes. Yet, there is considerable variation, with one country (Uruguay) having only two birthright-based acquisition modes in its citizenship law (citizenship by birth in the country, and via descent of a citizen for those born abroad), while Greece applies up to 23 out of a total possible 28 acquisition modes. Note that the top 5 countries with the highest number of acquisition modes are all European.

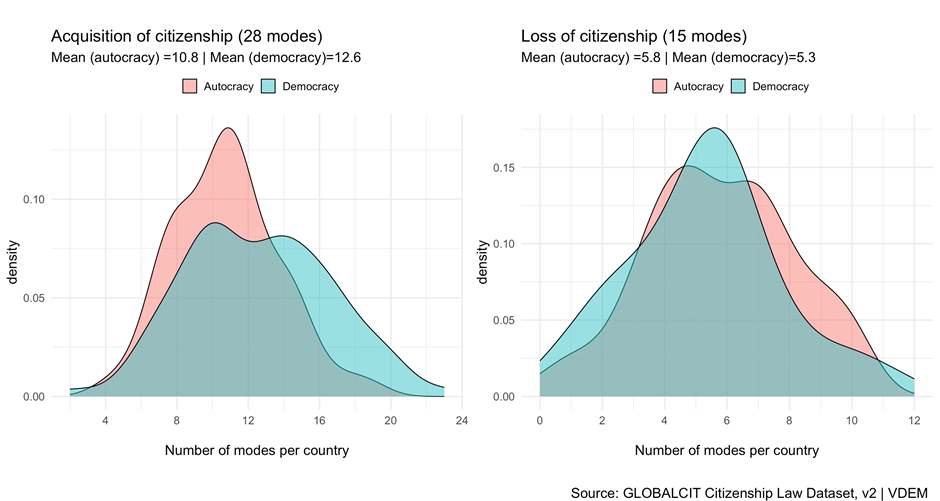

Next, by using iso country codes, the data can be merged with data from other sources, such as the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project, facilitating the exploration of patterns of citizenship law regulation by, for example, regime type. To provide one example, Figure 2 shows a density plot with the smoothed distribution of the number of acquisition and loss modes by country, by political regime. We see that on average, democracies have more applicable modes of acquisition of citizenship, but fewer applicable modes of loss of citizenship, compared to autocracies.

Figure 2. How many modes of acquisition and loss of citizenship, by political regime, in 2022?

Other ways to explore variation in citizenship law across political regimes would be to focus on inclusiveness of immigrant naturalisation (see e.g., Samuel Schmid’s Citizenship Regime Inclusiveness Index), or openness to voluntary renunciation (see a recent paper by Imke Harbers and Abbey Steele), for instance.

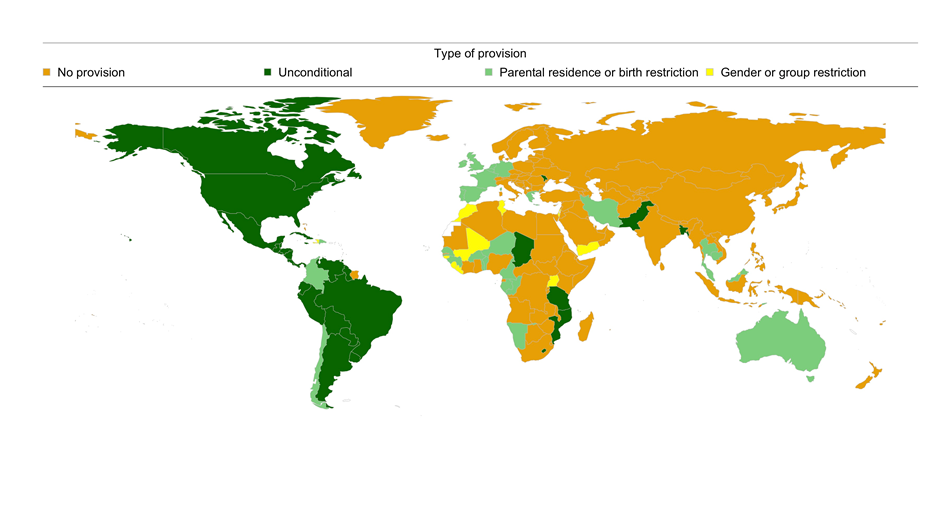

A new combined territorial birthright indicator

The Dataset also includes a new indicator (A02_cat) that provides a synthetic overview of relevant territorial birthright policies, combing information from modes A02a (territorial birthright irrespective of birthplace of the parents) and A02b (territorial birthright conditional on one or both parents also born in the country).

Figure 3 visualises the distribution of countries for a territorial birth-based acquisition of citizenship. We see that unconditional ius soli, such as mostly present in the Americas, may be exceptional, but is still present in up to 19 per cent of countries globally. Moreover, a form of conditional ius soli is present in another 17 per cent of countries, where children born in the territory only acquire the citizenship of that country, irrespective of the parental citizenship, if a parent is born on the territory or possesses a certain residence title. In 11 countries, parental gender or group restrictions apply (see here for a blog post by Bronwen Manby discussing discrimination in citizenship law).

Figure 3. Territorial birthright provisions around the world, 2022

source: GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset, v2, variable: A02_cat

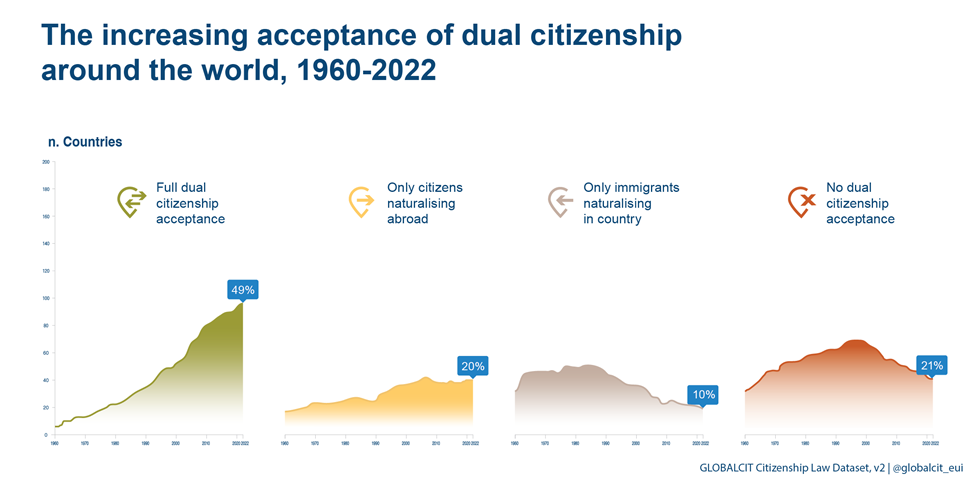

New longitudinal data on dual citizenship policies

Last but not least, in addition to data covering all modes of acquisition and loss of citizenship in 191 countries, version 2.0 of the main datafile (‘data_v2.0_country-year.csv’) also includes longitudinal data for the period 1960 – 2022 on three modes that are particularly relevant for dual citizenship acceptance: renunciation-requirement for residence-based acquisition (A06b), voluntary renunciation of citizenship (L01) and loss of citizenship due to the voluntary acquisition of another citizenship (L05). For the latter two modes of loss of citizenship, we build on previous work and incorporate the MACIMIDE Global Expatriate Dual Citizenship Dataset into the GLOBALCIT Dataset.

The longitudinal dual citizenship data cover an additional five micro-states (Andorra, Maldives, Monaco, San Marino, Vatican City State) and five predecessor states (Czechoslovakia, German Democratic Republic, Soviet Union, Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro)). In total, the data file includes 12664 rows with variable labels in the first row and 12663 country-year observations (201 states by 63 years). The sources for the coding of these dual citizenship provisions are included in a separate dual citizenship codebook, archived in the repository.

These data for the first time allow for a comprehensive analysis of global trends in the regulation of dual citizenship acceptance.

In Figure 4, the distribution of countries is visualised based on a variable (dualcit_comb) that combines information of one ‘acquisition’ and one ‘loss’ mode, which together reflect a country’s broad approach to dual citizenship acceptance upon naturalisation: mode A06b records whether a country requires applicants for naturalisation to renounce their previous citizenship (dual citizenship acceptance for persons naturalising in a country), while mode L05 records whether a citizen loses their citizenship if they voluntarily acquire another citizenship abroad.

In 2022, 49 percent of countries around the world fully accept dual citizenship, whereas only 21 percent consistently restrict dual citizenship at naturalisation. Almost a third of countries only accept dual citizenship for citizens naturalizing abroad (20 percent) or only for immigrants naturalizing in a country (10 percent).

Figure 4. Dual citizenship acceptance around the world, 1960 – 2022

Besides mapping the global trend and analysing determinants (see e.g., a paper analysing the international diffusion of expatriate dual citizenship policies), these data allow for the analysis of relevant outcomes, in particular migrant naturalisation behaviour, taking into account the dyadic nature of dual citizenship acceptance based on the constellation of origin country regulations (regarding loss of citizenship upon naturalizing abroad) and destination country rules (regarding the requirement to renounce one’s previous citizenship). See here, here, here and here examples of studies analysing the relevance of dual citizenship rules for migrant naturalisation behaviour (a forthcoming blog post in this series will discuss the dyadic nature of dual citizenship acceptance more extensively).

Where to go from here?

We aim to provide up-to-date information on citizenship laws, and our next update is foreseen for Spring 2024. Apart from updating, we are continuously working to back-code the data to offer information on citizenship law development across countries and over time, in order to facilitate trend analyses. Given the substantial work involved, we are only able to gradually expand the Dataset back in time for selected indicators, as with the dual citizenship information included in the latest update. In the coming years, we plan to expand the longitudinal coverage to birthright-based modes of acquisition (A01 – A05), residence-based citizenship acquisition (A06), facilitated citizenship acquisition by spouses/partners of citizens (A08), investor citizenship acquisition (A26), and security-based citizenship deprivation (L03, L04, L07, L08).

Access to the dataset: The GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset, version 2 can be explored in online databases here. The data and codebooks are archived in the EUI Research Data repository. The repository includes the most recent as well as previous iterations of the Dataset.

For a more elaborate introduction to the comparative methodology and presentation of some main patterns arising from the Dataset, see: Luuk van der Baaren and Maarten Vink, Modes of acquisition and loss of citizenship around the world: comparative typology and main patterns in 2020, GLOBALCIT Working Paper EUI RSC 2021-90. See here a blog introducing version 1 of the Dataset and here a contribution exploring the possibilities of the Dataset.